A Computer-age Doctor turns Athletes into Winners

Gideon Ariel is using computer technology to analyze athletes in action

By Ken Wilson in Enter on Sunday, July 1, 1984

A Computer-Age Doctor Turns Athletes into Winners

This article by Ken Wilson discusses how Dr. Gideon Ariel, a former Olympic discus thrower, uses computer technology to help athletes improve their performance. Dr. Ariel uses a system called the Digitizer, which applies the science of biomechanics to analyze an athlete's movements and identify areas for improvement. The Digitizer uses a high-speed camera to capture the athlete's movements, which are then analyzed on a video screen. The system has been used by several Olympians and professional athletes, including discus thrower Al Oerter, hurdler Edwin Moses, tennis star Jimmy Connors, and the U.S. Women's Volleyball team. Dr. Ariel also developed the Ariel-Tek, a computer-controlled exercise machine that helps athletes train more effectively. His future plans include using holography to create 3-D images of athletic performances for further analysis and training.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

A COMPUTER-AGE DOCTOR TURNSATHLETES INTO WINNERS

B Y K E N W I L S O N

0lympic gold medal winner Al Oerter is hurling the discus farther than ever-and he's got a joystick and video screen to thank for the improvement.

The U.S. Women's volleyball team went from being one of the worst to one of the top teams in the world-and they're getting help from the same system.

When you analyze athletics scientifically, you see that it is possible for many of the best athletes to do even better.

The system is called the Digitizer. The results are remarkable. Ask Olympians like hurdler Edwin Moses and discus thrower Mac Wilkens, or other great competitors like tennis star Jimmy Connors and marathon runner Bill Rodgers. Each has gotten help from the joystick-operated computerized Digitizer of Dr. Gideon Ariel.

"When you analyze athletics scientifically," says Dr. Ariel, "you see that it's possible for many of the best athletes to do even better."

ACTION ON SCREEN

As a former Olympic discus thrower, Gideon Ariel knows what it means to be a tough competitor. Since 1971, he has been using this knowledge and the science of biomechanics to help other athletes achieve their best performance.

Biomechanics is an attempt to apply the laws of physics to the human body, explains Ariel. "Sports problems should be treated like engineering problems. An engineer doesn't just guess that a bridge can hold up under traffic. She proves it mathematically.... We can do the same for athletes."

The main tool of biomechanics, the Digitizer, lets Dr. Ariel analyze an athlete's weaknesses. He can then go on and design ways to improve their performance. "Athletes are just too fast for the human eye to detect a problem,'

he says. The Digitizer can slow the action down and isolate any problems. The Digitizer alone will not turn a person into a great athlete. But it can provide information to enable good athletes to become even better.

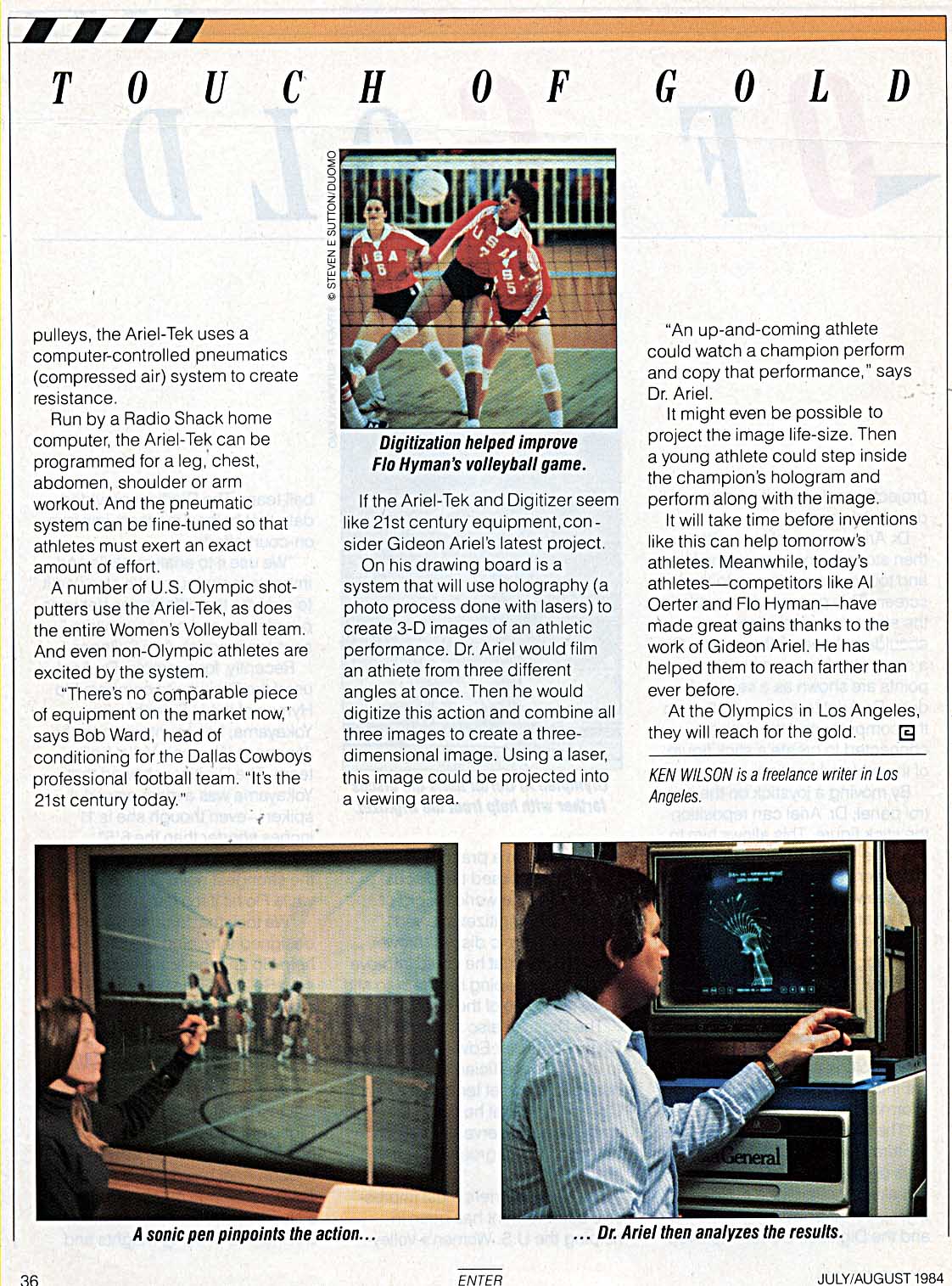

The digitizing process begins with a high-speed 16mm camera. This camera shoots up to 10,000 frames of film per second. An athlete comes to Dr. Ariel's Coto Research Center-a high-tech sports facility in southern Californiaand is filmed in action. Dr. Ariel runs this film through a stop-action

Or. Gideon Ariel is using computer technology to analyze athletes in action.

34

ENTER

.1LJIY/AIJGIJST 199

projector and views it on a specially designed screen.

Dr. Ariel-or one of his assistantsthen stops every frame of the film and touches a sonic pen to the screen. This pen makes a mark on the athlete's critical jointsshoulders, knees, elbows, etc. On a separate video monitor, these points are shown as a series of dots. Dr. Ariel touches a button on the computer and the dots are connected to create a stick figure of the athlete.in action.

By moving a joystick on the control panel, Dr. Ariel can reposition the stick figure. This allows him to examine the athlete's movement from every conceivable angle. "We can see what you're doing wrong and what you're doing right," explains Ariel. "Most important, we can suggest ways for you to improve."

GETTING RESULTS

Olympians and other athletes are impressed with the Digitizer's information.

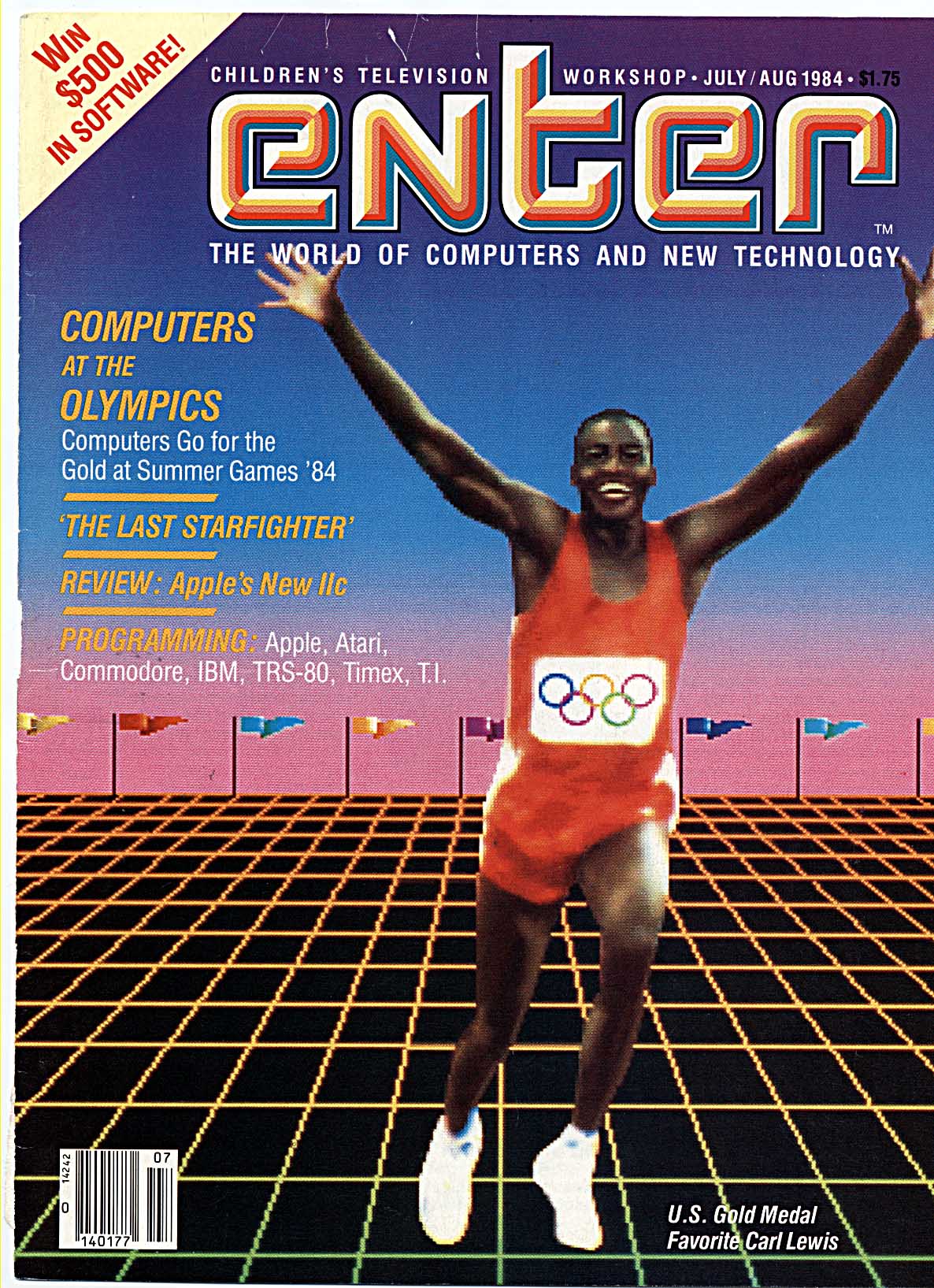

"The Digitizer helped me re-learn my throw, and it really paid off," says discus thrower Oerter, who has already competed in four Olympics. After working with Ariel and the Digitizer, Oerter improved

Olympian Al Oerter hurls the discus farther with help from the Digitizer.

enormously. In a practice session, Oerter even tossed the discus further than the world record of 233'5". The Digitizer showed another Olympic discus thrower, Mac Wilkins, that he could improve his toss by keeping his front leg stiff while letting go of the discus.

The Digitizer also showed Olympic hurdler Edwin Moses how to move more efficiently over the hurdles. And it let tennis pro Jimmy Connors see that he could strengthen his serve by keeping both feet on the ground when hitting the ball.

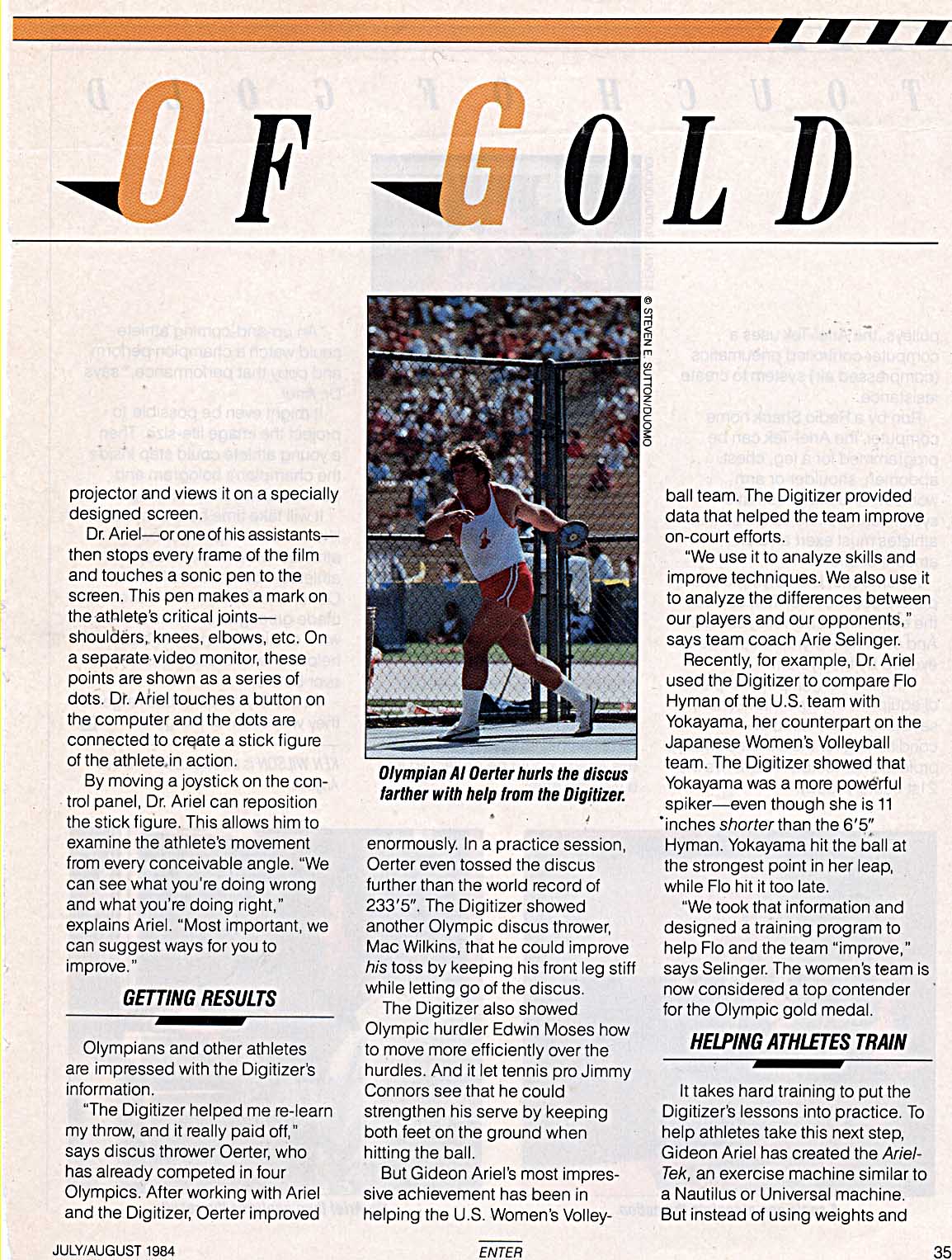

But Gideon Ariel's most impressive achievement has been in helping the U.S. Women's Volley

ball team. The Digitizer provided data that helped the team improve on-court efforts.

"We use it to analyze skills and improve techniques. We also use it to analyze the differences between our players and our opponents," says team coach Arie Selinger.

Recently, for example, Dr. Ariel used the Digitizer to compare Flo Hyman of the U.S. team with Yokayama, her counterpart on the Japanese Women's Volleyball team. The Digitizer showed that Yokayama was a more powerful spiker-even though she is 11 'inches shorter than the 6'5" Hyman. Yokayama hit the ball at the strongest point in her leap, while Flo hit it too late.

"We took that information and designed a training program to help Flo and the team "improve," says Selinger. The women's team is now considered a top contender for the Olympic gold medal.

HELPING ATHLETES TRAIN

It takes hard training to put the Digitizer's lessons into practice. To help athletes take this next step, Gideon Ariel has created the ArielTek, an exercise machine similar to a Nautilus or Universal machine. But instead of using weights and

JULY/AUGUST 1984

ENTER

35

Tl ff 1

T 0 U C H

pulleys, the Ariel-Tek uses a computer-controlled pneumatics (compressed air) system to create resistance.

Run by a Radio Shack home computer, the Ariel-Tek can be programmed for a leg, chest, abdomen, shoulder or arm workout. And the pneumatic system can be fine-tuned so that athletes must exert an exact amount of effort.

A number of U.S. Olympic shotputters use the Ariel-Tek, as does the entire Women's Volleyball team. And even non-Olympic athletes are excited by the system.

"There's no comparable piece of equipment on the market now,' says Bob Ward, head of conditioning for the Dallas Cowboys

professional football team. "It's the 21st century today."

Digitization helped improve Flo Hyman's volleyball game.

If the Ariel-Tek and Digitizer seem like 21st century equipment, consider Gideon Ariel's latest project.

On his drawing board is a system that will use holography (a photo process done with lasers) to create 3-D images of an athletic performance. Dr. Ariel would film an athlete from three different angles at once. Then he would digitize this action and combine all three images to create a threedimensional image. Using a laser, this image could be projected into a viewing area.

G 0 L D

"An up-and-coming athlete could watch a champion perform and copy that performance," says Dr. Ariel.

It might even be possible to project the image life-size. Then a young athlete could step inside the champion's hologram and perform along with the image.

It will take time before inventions like this can help tomorrow's athletes. Meanwhile, today's athletes-competitors like Al Oerter and Flo Hyman-have made great gains thanks to the work of Gideon Ariel. He has helped them to reach farther than ever before.

At the Olympics in Los Angeles, they will reach for the gold. 0

KEN WILSON is a freelance writer in Los Angeles.

0 F

A sonic pen pinpoints the action...

ENTER

JULY/AUGUST 1984