Can a Computer develop a Champion?

It's been my dream since starting to work with my associate, Dr. Gideon Ariel, director of the Coto Research Center, to have a tennis player turn himself over to science

By Vic Braden in Tennis on Friday, June 1, 1984

In the article "Can a Computer Develop a Champion?" by Vic Braden, the author explores the use of technology in improving the performance of tennis players. The article focuses on Hu Na, a Chinese tennis player who defected to the U.S. in 1982. Braden and his associate, Dr. Gideon Ariel, use sophisticated computerized exercise machines and high-speed cameras to analyze Hu Na's strengths, weaknesses, and technique. The data gathered is used to create a personalized training program for Hu Na, which includes changes to her grip, backswing, and serve. The article concludes by noting that while technology can significantly improve a player's physical performance, it cannot enhance their confidence or manage their nervousness during a match.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

CAN A COMPUTER DEVELOPA CHAMPION?

BY VIC BRADEN, Instruction Editor

hen Hu Na, the Chinese tennis player, defected from her country in 1982, she

had a tremendous burden to carry. She was famous before she had learned how to be a professional tennis player. So she had to do it in the full glare of national publicity.

It was really unfair, because she never asked to be treated specially; she just wanted to make a new life in the U.S. But the media went crazy. Tournament officials gave her special treatment, which she never requested and which didn't win her any friends 'among the other players.

It's been my dream since starting to work with my associate, Dr. Gideon Ariel, director of the Coto Research Center, to have a tennis player turn himself over to science, and let us and science make him a better player. So I was thrilled when Hu Na came to me last winter with the willingness to do just that, and an incredible desire to become a tennis player who could live up to the publicity she'd already received.

Martina Navratilova knows the value of science, but there are still skeptics out there. In fact, Navratilova has just scratched the surface when it comes to using computers to help make a champion.

My first concern, though, was for Hu Na as a person. Here was a

young woman of 21 who had

entered our society as the object of an international cause celebre. tier defection severely strained relations between her country and ours.

But I found that she's a fighter with the will to overcome any obstacles. She's also intelligent, learns fast and, this is particularly important, was the first to admit she needed help. I simply said: "Look, I don't know if I can help you because

0 TF\VI',I,.-i�"$4

the fact is, in my opinion, you don't know how to play."

You can't be phony. You and a computer are not going to help a player grow by telling him or her a lie. Hu Na just bit her lip and proceeded to accept the many tough things we threw at her.

We first had to find out just what she knew about the game of tennis. She had little knowledge about the biornechanics, the engineering of the game. But that's not unusual. Most players don't have any idea how muscle systems work to stroke a ball.

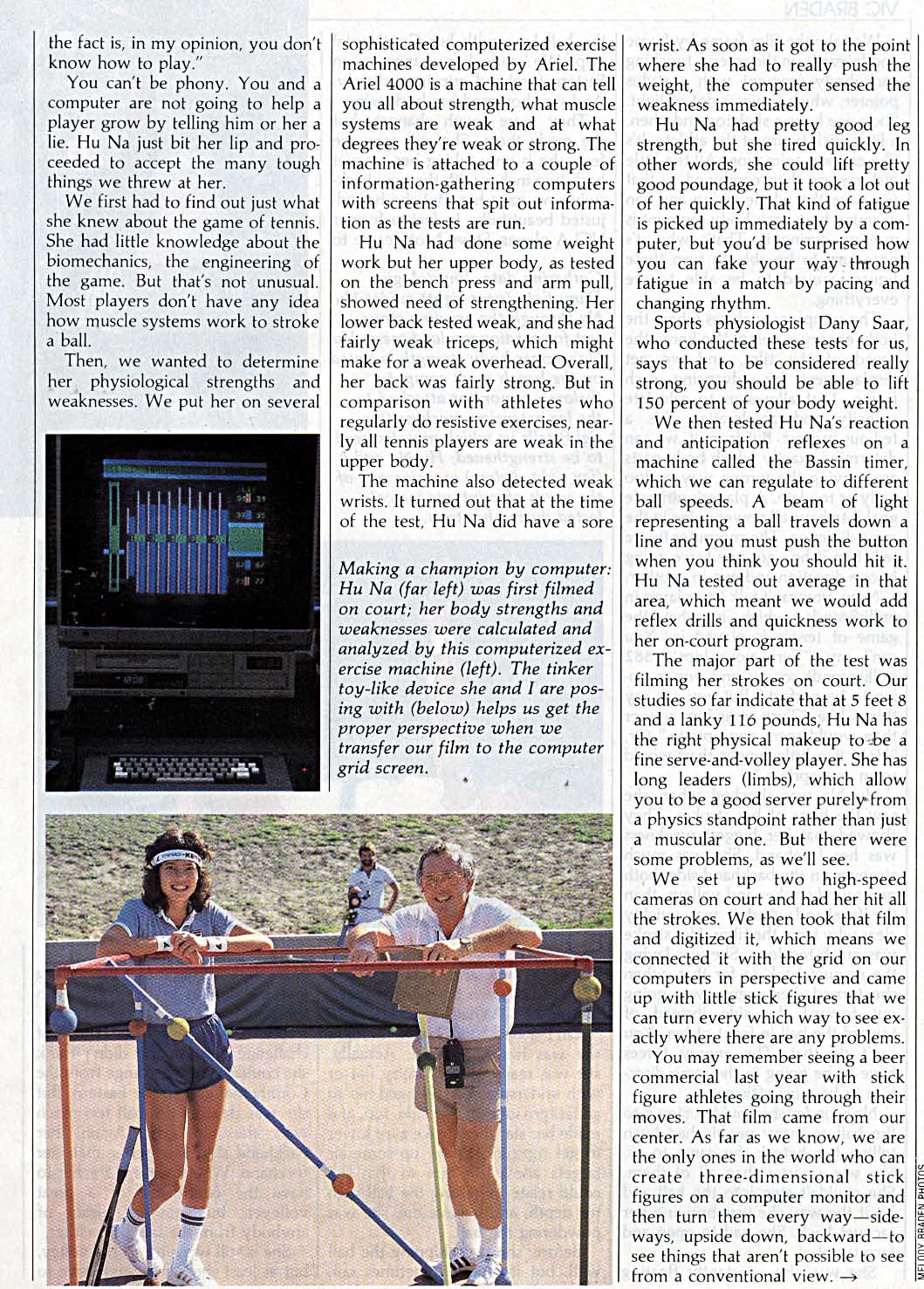

Then, we wanted to determine her physiological strengths and weaknesses. We put her on several

sophisticated computerized exercise machines developed by Ariel. The Ariel 4000 is a machine that can tell you all about strength, what muscle systems are weak and at what degrees they're weak or strong. The machine is attached to a couple of information-gathering computers with screens that spit out information as the tests are run.

Hu Na had done some weight work but her upper body, as tested on the bench press and arm pull, showed need of strengthening. Her lower back tested weak, and she had fairly weak triceps, which might make for a weak overhead. Overall, her back was fairly strong. But in comparison with athletes who regularly do resistive exercises, nearly all tennis players are weak in the upper body.

The machine also detected weak wrists. It turned out that at the time of the test, Hu Na did have a sore

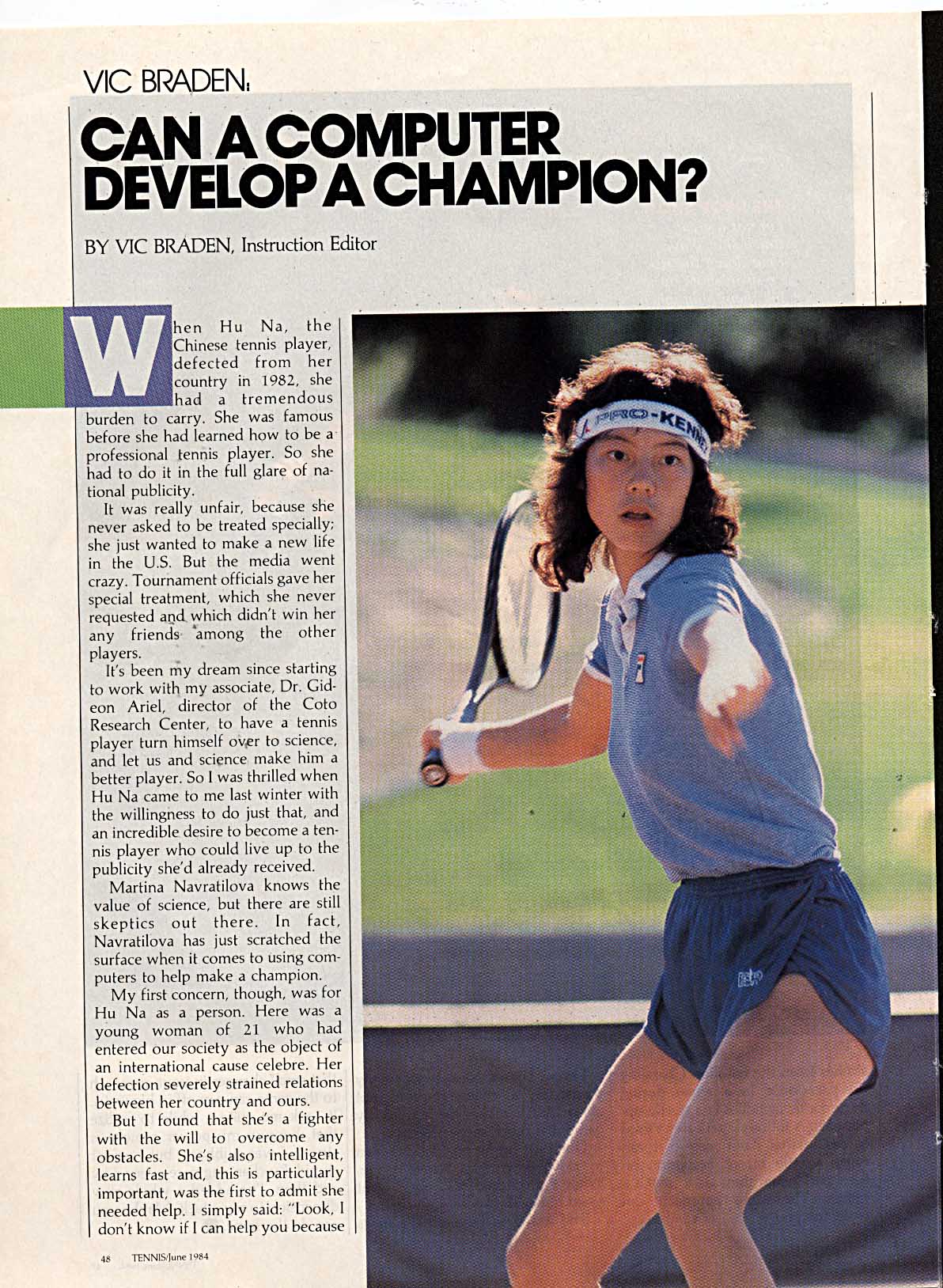

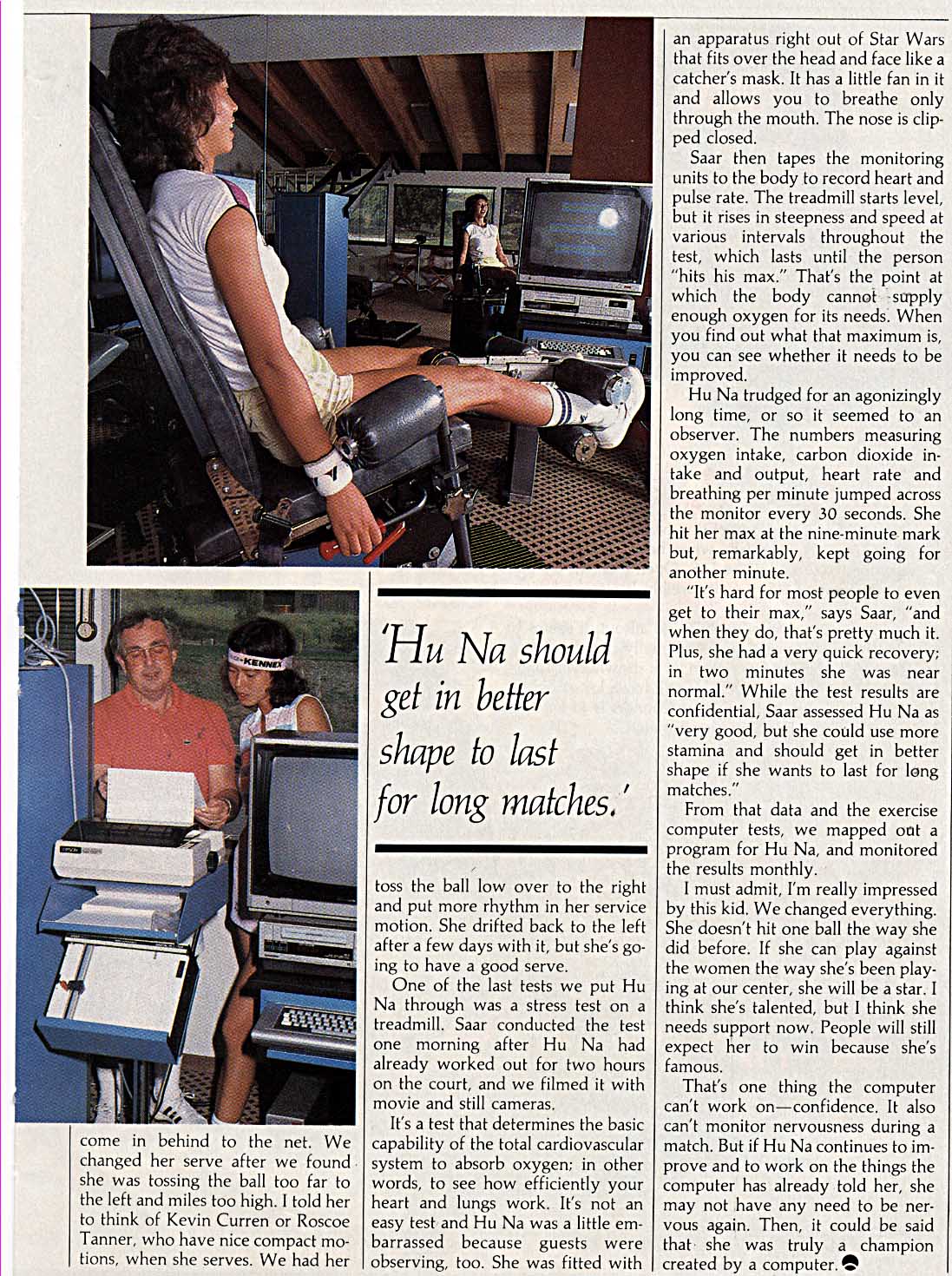

Making a champion by computer: Hu Na (far left) was first filmed on court; her body strengths and weaknesses were calculated and analyzed by this computerized exercise machine (left). The tinker toy-like device she and I are posing with (below) helps us get the proper perspective when we transfer our film to the computer grid screen.

wrist. As soon as it got to the point where she had to really push the weight, the computer sensed the weakness immediately.

Hu Na had pretty good leg strength, but she tired quickly. In other words, she could lift pretty good poundage, but it took a lot out of her quickly. That kind of fatigue is picked up immediately by a computer, but you'd be surprised how you can fake your way through fatigue in a match by pacing and changing rhythm.

Sports physiologist Dany Saar, who conducted these tests for us, says that to be considered really strong, you should be able to lift 150 percent of your body weight.

We then tested Hu Na's reaction and anticipation reflexes on a machine called the Bassin tinier, which we can regulate to different ball speeds. A beam of light representing a ball travels down a line and you must push the button when you think you should hit it. Hu Na tested out average in that area, which meant we would add reflex drills and quickness work to her on-court program.

The major part of the test was filming her strokes on court. Our studies so far indicate that at 5 feet 8 and a lanky 116 pounds, Hu Na has the right physical makeup to -be a fine serve-and-volley player. She has long leaders (limbs), which allow you to be a good server purely from a physics standpoint rather than just a muscular one. But there were some problems, as we'll see.

We set up two high-speed cameras on court and had her hit all the strokes. We then took that film and digitized it, which means we connected it with the grid on our computers in perspective and came up with little stick figures that we can turn every which way to see exactly where there are any problems.

You may remember seeing a beer commercial last year with stick figure athletes going through their moves. That film came from our center. As far as we know, we are the only ones in the world who can create three-dimensional stick figures on a computer monitor and then turn them every way-sideways, upside down, backward-to see things that aren't possible to see from a conventional view. -

VIC BRADEN

We take the film frame by frame and freeze it on the screen, touching each body segment with a stylus pointer, which leaves a dot of light. Soon, we have a skeleton and, then, a little stick figure of the athlete. It's like cartoon animation. All the little pictures are then combined so that we have the whole swing and can examine how each body segment is moving during it. That's why it's necessary to be able to turn these figures around to be able to see everything.

The computer analyzes where the body energy is going. We know the speed of the film, and we get displacement by advancing each frame. That allows us to calculate velocity and acceleration. It's a tedious process. But from it, we can determine exactly which body parts are moving the wrong way or too early or too late. A player's ultimate goal is to have all power going in the same direction. The computer figure tells him if he's got one force going in one direction and one in another.

Now, you can't talk to a player in milliseconds, which is what the game of tennis is played in. You can't say, "Turn your hips 1,882 milliseconds sooner and you're going to be perfect." But you can say things like, "Turn your hips sooner than would seem appropriate." Or, "Hold it a little longer than would seem appropriate."

Hu Na was shocked when she saw the films of her strokes. They showed that her biggest weakness was her forehand. She was much stronger on the backhand side, both on ground strokes and volleys, than the forehand. And it was quickly clear why from the films. Her stroke was much too long. She was laying the racquet back so far that, when she turned, her energy was going out toward the side instead of toward the ball in front of her. You can't do that. The energy forces have to be going in the same direction to be most efficient.

No wonder she couldn't step into the ball as many people had been telling her before she came to us. She was smarter than all of them. She couldn't step into the ball and hit it the way she was bringing her racquet back. She had to open and face the shot.

the ball long with her Continental grip. We made her change to an Eastern forehand grip immediately. And we shortened her backswing.

They were tough changes, but she made them. She still says she feels she is only taking her racquet back two inches with the new backswing we gave her. But she has adjusted beautifully. In fact, a former UCLA player, Steve Mott, came to

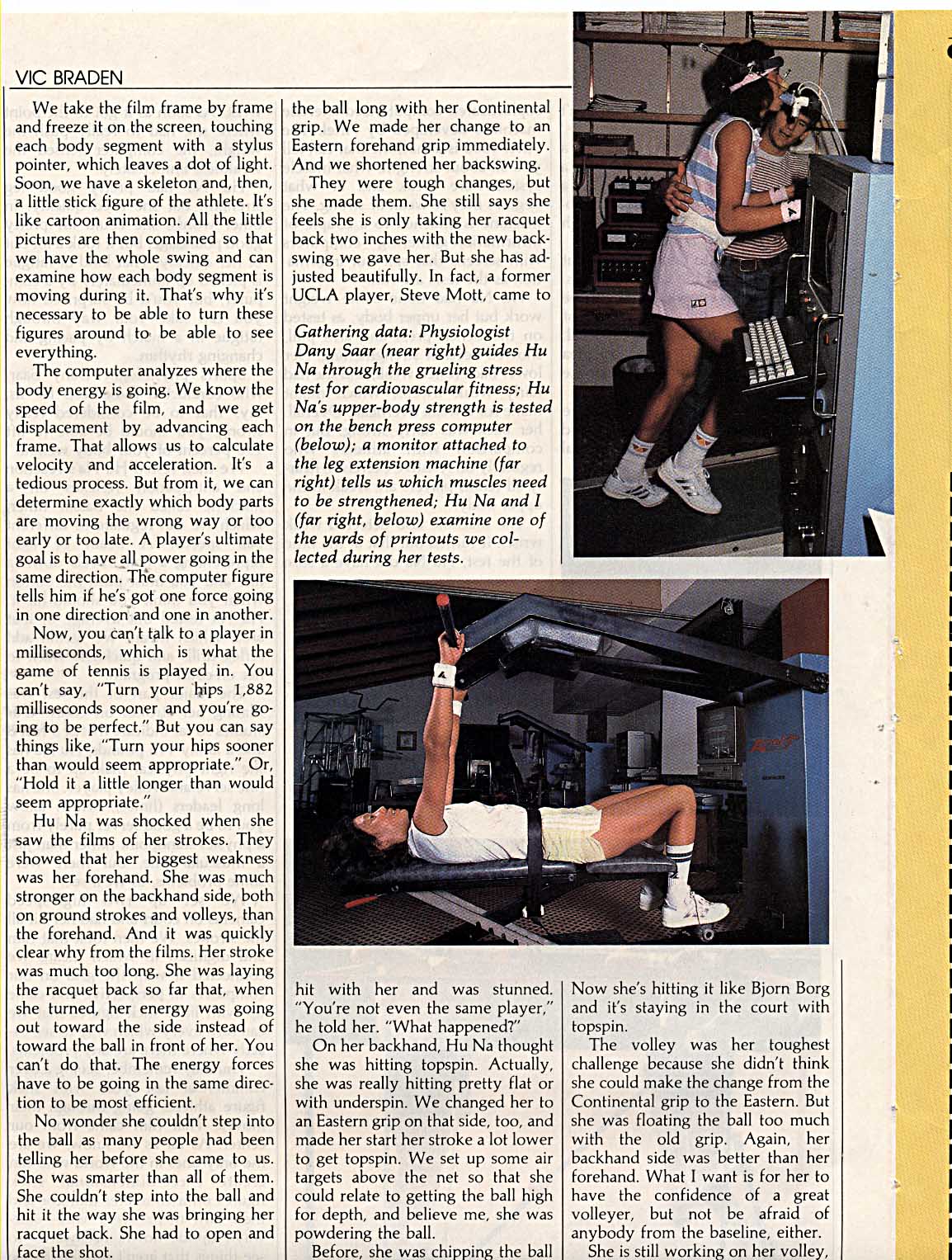

Gathering data: Physiologist Dany Saar (near right) guides Hu Na through the grueling stress test for cardiovascular fitness; Hu Na's upper-body strength is tested on the bench press computer (below); a monitor attached to the leg extension machine (far right) tells us which muscles need to be strengthened; Hu Na and I (far right, below) examine one of the yards of printouts we collected during her tests.

hit with her and was stunned. "You're not even the same player," he told her. "What happened?"

On her backhand, Hu Na thought she was hitting topspin. Actually, she was really hitting pretty flat or with underspin. We changed her to an Eastern grip on that side, too, and made her start her stroke a lot lower to get topspin. We set up some air targets above the net so that she could relate to getting the ball high for depth, and believe me, she was powdering the ball.

Before, she was chipping the ball

Now she's hitting it like Bjorn Borg and it's staying in the court with topspin.

The volley was her toughest challenge because she didn't think she could make the change from the Continental grip to the Eastern. But she was floating the ball too much with the old grip. Again, her backhand side was better than her forehand. What I want is for her to have the confidence of a great volleyer, but not be afraid of anybody from the baseline, either.

She is still working on her volley,

come in behind to the net. We changed her serve after we found she was tossing the ball too far to the left and miles too high. I told her to think of Kevin Curren or Roscoe Tanner, who have nice compact motions, when she serves. We had her

toss the ball low over to the right and put more rhythm in her service motion. She drifted back to the left after a few days with it, but she's going to have a good serve.

One of the last tests we put Hu Na through was a stress test on a treadmill. Saar conducted the test one morning after Hu Na had already worked out for two hours on the court, and we filmed it with movie and still cameras.

It's a test that determines the basic capability of the total cardiovascular system to absorb oxygen; in other words, to see how efficiently your heart and lungs work. It's not an easy test and Hu Na was a little embarrassed because guests were observing, too. She was fitted with

an apparatus right out of Star Wars that fits over the head and face like a catcher's mask. It has a little fan in it and allows you to breathe only through the mouth. The nose is clipped closed.

Saar then tapes the monitoring units to the body to record heart and pulse rate. The treadmill starts level, but it rises in steepness and speed at various intervals throughout the test, which lasts until the person "hits his max." That's the point at which the body cannot supply enough oxygen for its needs. When you find out what that maximum is, you can see whether it needs to be improved.

Hu Na trudged for an agonizingly long time, or so it seemed to an observer. The numbers measuring oxygen intake, carbon dioxide intake and output, heart rate and breathing per minute jumped across the monitor every 30 seconds. She hit her max at the nine-minute mark but, remarkably, kept going for another minute.

"It's hard for most people to even get to their max," says Saar, "and when they do, that's pretty much it. Plus, she had a very quick recovery; in two minutes she was near normal." While the test results are confidential, Saar assessed Hu Na as "very good, but she could use more stamina and should get in better shape if she wants to last for long matches."

From that data and the exercise computer tests, we mapped oat a program for Hu Na, and monitored the results monthly.

I must admit, I'm really impressed by this kid. We changed everything. She doesn't hit one ball the way she did before. If she can play against the women the way she's been playing at our center, she will be a star. I think she's talented, but I think she needs support now. People will still expect her to win because she's famous.

That's one thing the computer can't work on-confidence. It also can't monitor nervousness during a match. But if Hu Na continues to improve and to work on the things the computer has already told her, she may not have any need to be nervous again. Then, it could be said that she was truly a champion created by a computer.

'Hu Na should

get in better

shape to last

for long matches.'