Medicine Catches up with the Sports Boom

humans need to keep the body-machine in trim to achieve a sense of physical and mental well-being

By Unknown in The New York Times Magazine on Wednesday, October 1, 1980

The article discusses the importance of physical fitness and the role of sports medicine in achieving it. It highlights the issue of sports injuries among children, often due to pressure from parents or coaches, and the mismatch of body types to certain sports. The article introduces Dr. Gideon Ariel's technique of "computerized biomechanical analysis" which can detect subtle elements of pathology that may not be visible to the naked eye. The article also mentions the work of Dr. David L. Costill, who found that caffeine can improve endurance during exercise. The article concludes by discussing the increasing interest in fitness and the role of the American Association of Fitness Directors in promoting health and fitness in the corporate world.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

UP WITH .MEDICINE CATCHES SPORTS sooM

humans need to keep the body-machine in trim to achieve a sense of physical and mental well-being - and that this can be done by putting it in rhythmic motion as much as possible, in accordance with one's individual capacity. It's quite normal, the experts insist, to begin exercising regularly when you're still a child - and to realize that people over 40 are capable of attaining fitness goals that, only a few years ago, might have been considered beyond their reach.

Each year, as many as 10 million injuries of all kinds occur among the 20 million to 25 million American children who are involved in sports. Often, these injuries occur because youngsters have been pressured to play contact sports by thoughtless parents, or by coaches whose only goal is that of winning. Sports scientists say that, too often, children are encouraged to play beyond their capacity in games that are wrong for their body types. But, the experts say, adequate "physical profiling" of these children would have made it clear beforehand that they were engaging in sports for which they were probably unsuited - as, for example, when someone with a lean sprinter's physique is steered toward weight-lifting or ice hockey, or when a heavy-boned, youngster is pushed toward competition in tennis or in the 100-yard dash instead of in football or rugby.

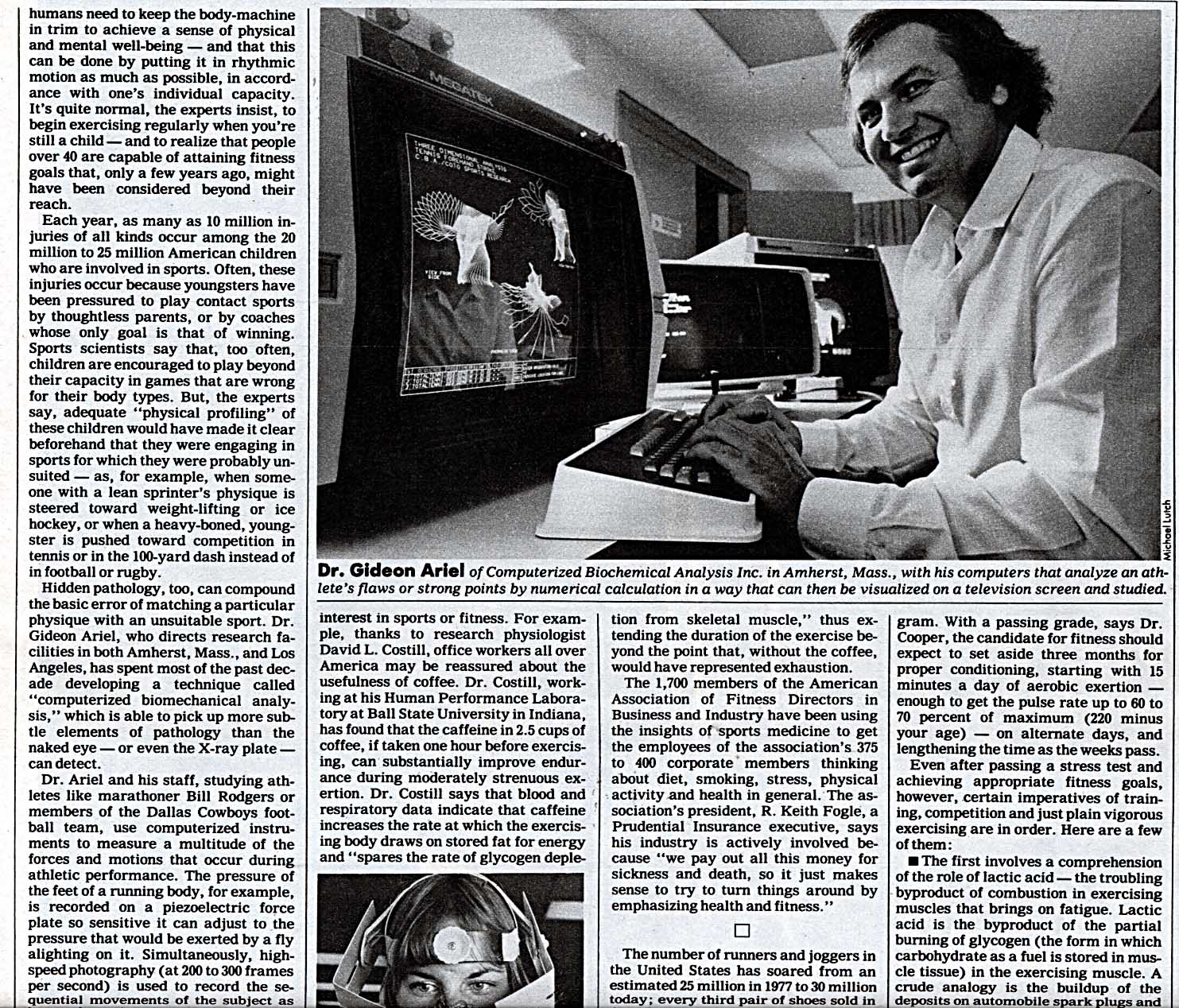

Hidden pathology, too, can compound the basic error of matching a particular physique with an unsuitable sport. Dr. Gideon Ariel, who directs research facilities in both Amherst, Mass., and Los Angeles, has spent most of the past decade developing a technique called "computerized biomechanical analysis," which is able to pick up more subtle elements of pathology than the naked eye - or even the X-ray plate - can detect.

Dr. Ariel and his staff, studying athletes like marathoner Bill Rodgers or members of the Dallas Cowboys football team, use computerized instruments to measure a multitude of the forces and motions that occur during athletic performance. The pressure of the feet of a running body, for example, is recorded on a piezoelectric force plate so sensitive it can adjust to the pressure that would be exerted by a fly alighting on it. Simultaneously, highspeed photography (at 200 to 300 frames per second) is used to record the sequential movements of the subject as

interest in sports or fitness. For example, thanks to research physiologist David L. Costill, office workers all over America may be reassured about the usefulness of coffee. Dr. Costill, working at his Human Performance Laboratory at Ball State University in Indiana, has found that the caffeine in 2.5 cups of coffee, if taken one hour before exercising, can substantially improve endurance during moderately strenuous exertion. Dr. Costill says that blood and respiratory data indicate that caffeine increases the rate at which the exercising body draws on stored fat for energy and "spares the rate of glycogen deple

tion from skeletal muscle," thus extending the duration of the exercise beyond the point that, without the coffee, would have represented exhaustion.

The 1,700 members of the American Association of Fitness Directors in Business and Industry have been using the insights of sports medicine to get the employees of the association's 375 to 400 corporate members thinking about diet, smoking, stress, physical activity and health in general. The association's president, R. Keith Fogle, a Prudential Insurance executive, says his industry is actively involved because "we pay out all this money for sickness and death, so it just makes sense to try to turn things around by emphasizing health and fitness."

0

The number of runners and joggers in the United States has soared from an estimated 25 million in 1977 to 30 million today; every third pair of shoes sold in

gram. With a passing grade, says Dr. Cooper, the candidate for fitness should expect to set aside three months for proper conditioning, starting with 15 minutes a day of aerobic exertion - enough to get the pulse rate up to 60 to 70 percent of maximum (220 minus your age) - on alternate days, and lengthening the time as the weeks pass.

Even after passing a stress test and achieving appropriate fitness goals, however, certain imperatives of training, competition and just plain vigorous exercising are in order. Here are a few of them:

The first involves a comprehension of the role of lactic acid - the troubling byproduct of combustion in exercising muscles that brings on fatigue. Lactic acid is the byproduct of the partial burning of glycogen (the form in which carbohydrate as a fuel is stored in muscle tissue) in the exercising muscle. A crude analogy is the buildup of the deposits on automobile spark plugs and

Dr. Gideon Ariel of Computerized Biochemical Analysis Inc. in Amherst, Mass., with his computers that analyze an athlete's flaws or strong points by numerical calculation in a way that can then be visualized on a television screen and studied