Gideon Ariel Reigns Over Biomechanical Xanadu

Sports-related companies to design, research and test new products

By Richard Leivenberg in Footwear on Friday, January 1, 1982

Dr. Gideon Ariel, a scientist in the field of biomechanics, is revolutionizing the sports industry with his innovative designs and research. Working from his Coto Research Center, Ariel uses high-speed cameras and customized computers to analyze athletic performance and devise ways to improve it. His work includes designing a computerized running shoe, hydraulic exercise equipment, and researching how color affects an athlete's mood. Ariel's methodology is currently being used at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, and he has worked with various sports-related companies to design, research, and test new products. His work aims to defy randomness and gain control of the body and mind through biomechanics.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

Footwear

Gideon A riel Reigns Over Biomechanical Xanadu

sports-related companies to design, research and test new products. "One company even paid me not to design a shoe for them or to sell the idea. They said it would be too revolutionary. Can you believe it?"

If anything, Ariel and his 12 computers assuredly are revolutionary. The Coto Research Center includes a 200-meter indoor-outdoor track made of an Ariel-designed combination of old tires, cement and sawdust. But the real. feature is the eight pressure plates connected to the computer complex, which give Ariel a wealth of data about how the body runs. More than 10,000 manhours and $2 million have been put into devising the programs that analyze athletes.

On a typical day, everything seems to be happening at once. Ariel is meeting with cofounder/psychologist/tennis teacher extraordinaire - Vic Braden on how best to relay their findings to coaches at the National Coaches Convention March 26 in Chicago. He's having lunch with the editor of his five-year treatise, tentatively titled Optimum, to be published in 1982. A computer consultant awaits his decision on a new set of programs, and a reporter wishes yet another interview with a man who is like some 20th century wizard.

"It's crazy here, yes?," he asked behind an obviously proud grin. The craziness, however, is only on the surface.

"The whole idea is to defy ran- y domness, gain control of the ,~ body and mind through biome- ,~ chanics," he said of his science. "Biomechanics measures output, and our relationship with '

science_ f mlai�h.medicinea.hut___mr._an.vrnnmant._ia_thrnnoh ., .

BY RICHARD LEIVENBERG

TROBUCO CANYON, Calif.Dr. Gideon Ariel has designed a computerized running shoe that will be on the market in six months. His hydraulic exercise equipment, complete with video screen and keyboard, will be marketed by Wilson Sporting Goods. He is currently working on discovering how color affects an athlete's mood. And, he is trying to determine how to control an athlete's fear of his opponent and how to increase his drive.

Working out of his specially designed computer/exercise laboratories, hidden away within a secretive, sprawling resort called Coto de Caza, Ariel seems like some modern day mad scientist. He isn't mad, although some might think so. But he is a scientist. In the field of biomechanics. From his Coto Research Center, Ariel asks and answers some of the questions that confront athletes and coaches in their attempts to better performance. With his highspeed cameras and customized computers and digitizers, Ariel is discovering how fast a swimmer can swim, how high a volleyball player can leap, how far a human can throw a javelin, toss a football, pitch a baseball and on and on. The multitude of questions to be answered is overwhelming, but all have answers, according to the man behind the computer. All can be solved via biomechanics.

"Biomechanics should not be

confused with sports medicine,"

said the one time Olympic

discus thrower. This is sport

want to change. But, we want the feedback. We want our ideas to be tested, used and challenged," said Braden, who has proposed a weekly television series to the networks on the subject of biomechanics that he hopes will air this year.

In Chicago, Ariel, Braden and a team of other sports experts will present their biomechanical principles to coaches in a day and a half worth of seminars and demonstrations.

"We want to take science to the coaches. They ask how they can make their athletes jump higher or run faster. We can tell them," said Braden, who also runs the Tennis College here.

Recently, the U.S. Women's Volleyball team competed in a world meet and finished second.

P_

movement. "There really is no magic here. It is only high school physics applied via today's technology," he said, trying to demystify his method. In one computer-crammed room, a bearded man named Justin programs the day's message. He once worked on programming of the missiles that defend our country. "Now, he is in the real world," laughed Ariel.

That real world -includes the design of better sports equipment and clothing. By applying biomechanics to clothing design, Ariel can determine if tight pants interfere with activity, how friction slows swimming and how air resistance hinders sprinting. He can also measure how certain

And, from Ariel's hi-tech world comes the computerized shoe. "Slip a computer chip into the shoe before you run: When you return from your exercise, insert the chip into your home computer and you will find out how far you really ran, how much energy was spent, how long you were in the air, how you hit the ground and whether you should alter your training to shorter distances at a faster pace," he explained.

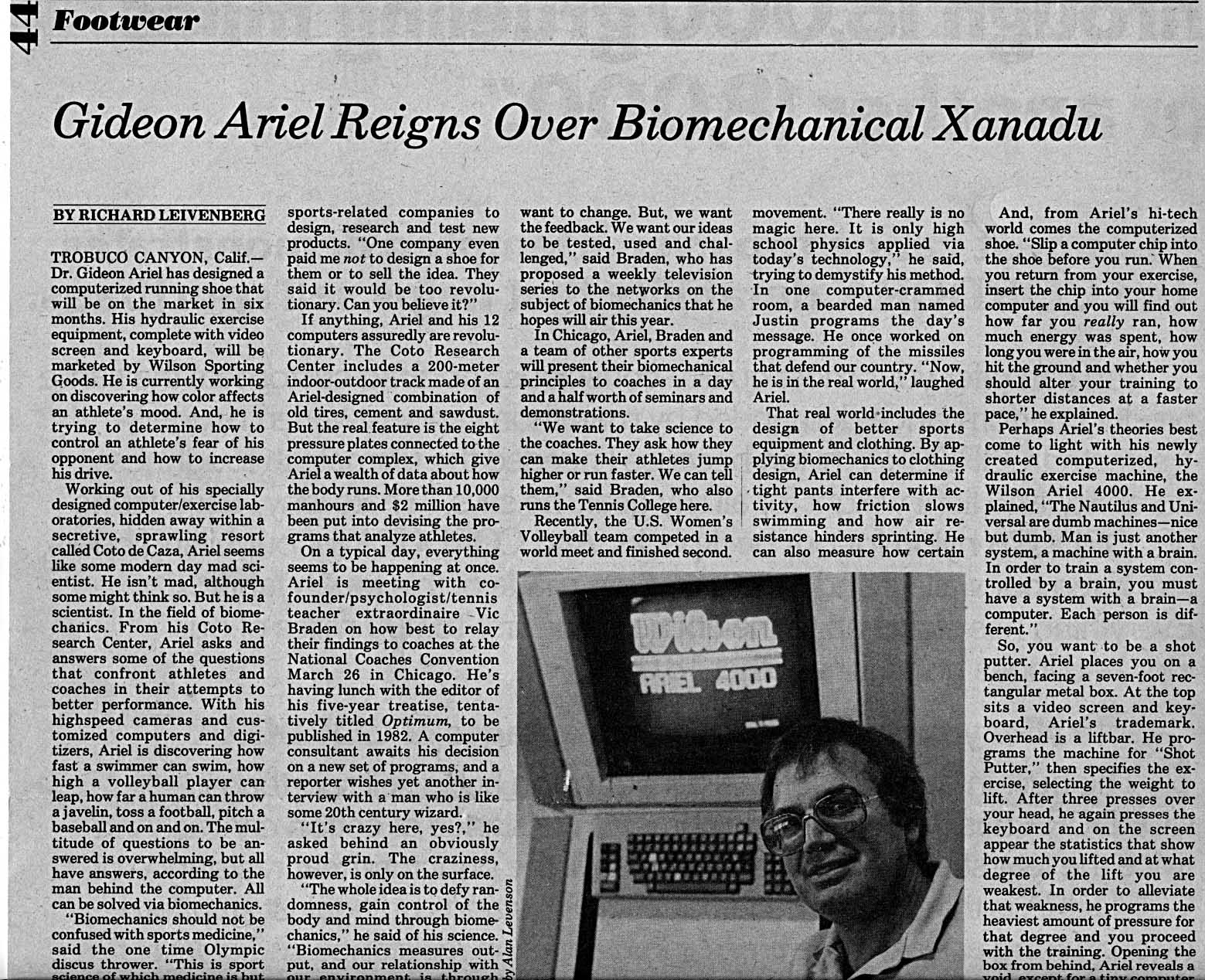

Perhaps Ariel's theories best come to light with his newly created computerized, hydraulic exercise machine, the Wilson Ariel 4000. He explained, "The Nautilus and Universal are dumb machines-nice but dumb. Man is just another system, a machine with a brain. In order to train a system controlled by a brain, you must have a system with a brain-a computer. Each person is different."

So, you want to be a shot putter. Ariel places you on a bench, facing a seven-foot rectangular metal box. At the top sits a video screen and keyboard, Ariel's trademark. Overhead is a liftbar. He programs the machine for "Shot Putter," then specifies the exercise, selecting the weight to lift. After three presses over your head, he again presses the keyboard and on the screen appear the statistics that show how much you lifted and at what degree of the lift you are weakest. In order to alleviate that weakness, he programs the heaviest amount of pressure for that degree and you proceed with the training. Opening the box from behind, Ariel reveals a

void a:oant_ far a tine, anmnntar....

GVU LL 111 I, l lL- LlLLVLUk)Ltf LV

better performance. With his highspeed cameras and customized computers and digitizers, Ariel is discovering how fast a swimmer can swim, how high a volleyball player can leap, how far a human can throw a javelin, toss a football, pitch a baseball and on and on. The multitude of questions to be answered is overwhelming, but all have answers, according to the man behind the computer. All can be solved via biomechanics.

"Biomechanics should not be confused with sports medicine," said the one time Olympic discus thrower. "This is sport science of which medicine is but one part. We are not dealing with athletes who are ill, although we can aid in rehabilitation. We are dealing with super athletes."

One of Ariel's favorite subjects is Flo Hyman, a woman of towering dimensions. The 6'6' 27-year-old is a seven year veteran of the U.S. Women's Volleyball team. This year she became the world's top woman spiker, in part because she can elevate herself 38 inches off the floor. Said Hyman, whose team is coached by physiologist Dr. Arie Selinger, "Sometimes you just don't believe it (what you can do) until you see it on video."

Hyman is but one of many who have worked with Ariel over the last five years to improve their form. Currently, Ariel's methodology is being used at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Col. He has worked with individuals like discus thrower Mac Wilkens and teams like the Kansas City Royals. He has even aided the Space Program. "We had Gordon Cooper here to test his reaction time. We can tell who the best pilot is or if that person should even be a pilot," said the ever-confident Ariel.

Ariel has variously been sponsored by AMF, Wilson, Spalding, Pony and numerous

navlng luncn Wall Lile eulLVr VI

his five-year treatise, tentatively titled Optimum, to be published in 1982. A computer consultant awaits his decision on a new set of programs, and a reporter wishes yet another interview with a man who is like some 20th century wizard.

"It's crazy here, yes?," he asked behind an obviously proud grin. The craziness, however, is only on the surface.

"The whole idea is to defy ran- y domness, gain control of the o" body and mind through biome- - chanics," he said of his science. '~ "Biomechanics measures out- 3 P put, and our relationship with �a, our environment is through .o . output not input." o

An Israeli, Ariel competed in ,4 the 1960 and 1964 Olympics and ' still holds the discus record for hfs native country. "Ninety-five per cent of what I learned as far as training was good English BS," said the always candid Ariel. "Just to run 10 miles a day is not enough."

So, Ariel, schooled in Exercise Science at the University of Massachusetts, began examining, then destroying the myths that pervade athletic training.

"Everyone has always thought that to jump highest you must bend your knees. The more you bend, the higher you get. This is not so," said volleyball coach Selinger, who is also a member of the Coto team. "Rather than a fluid motion in which the spiker absorbs then leaps, we want her to hit the floor hard, then leap, bending the knees as little as possible."

Another myth, Ariel contends, is the- vaunted followthrough. "In golf, it is the whip and downswing, not the followthrough that is important," claimed Ariel, who once analyzed Jack Nicklaus's swing. "Acceleration-deceleration is what counts most."

Both Ariel and Braden know they have a credibility problem. "Anytime there is something new, there are those who don't

fabrics can help maintain, reduce or increase the body temperature. Also, he believes that certain colors will make an opponent angry or upset his concentration.

Then there is the running shoe. The affable Ariel smiles once again when considering a market that he sees as beleagured by monotony and inefficiency. "Those shoe ratings make me laugh," he said. "What is good for one person is not necessarily good for another. It doesn't make sense to search for a shoe that may be one ounce lighter than another. Sprinters need lightness. Runners who run for exercise do not. Your feet may lose 16 ounces of sweat alone, so what does one ounce matter?"

Ariel, who has designed shoes for Pony and J.C. Penney ("The Penney Olympic model is as good as any Nike.") foresees an inflatable shoe that conforms to each person's traits. "The inflatable shoe can be adjusted to the amount of pressure being applied," he said. "A person who weighs 150 pounds exerts a different amount of pressure than one who weighs 200 pounds."

wbww a aw vva. � s, vY

sits a video screen and keyboard, Ariel's trademark. Overhead is a liftbar. He programs the machine for "Shot Putter," then specifies the exercise, selecting the weight to lift. After three presses over your head, he again presses the keyboard and on the screen appear the statistics that show how much you lifted and at what degree of the lift you are weakest. In order to alleviate that weakness, he programs the heaviest amount of pressure for that degree and you proceed with the training. Opening the box from behind, Ariel reveals a void, except for a tiny computer chip which runs the machine.

The cost will run around $1000 for the first Wilson Ariel 4000. "There will be diagnostic cassettes for each person to buy on a regular basis. There will be cassettes for every sport," he said. "It is a flexible machine much like the human body."

Ariel's theory is the soul of simplicity. "Gravity is always the same, but athletes are always trying to defy gravity. So, we calculate the forces it takes to conquer gravity. We change their form, alter their training, even change the diet, if necessary." Ariel recently came out with his own brand of vitamins as well.

The principles of motion have been known for years, but it has taken computers and cameras to apply them properly to the human body and mind. And, it has taken Gordon Ariel, today's athlete-scientist, to help bring them to the public, with applications that are extremely farreaching.

In his book, Optimum, now in manuscript form, Ariel will present his ideas in layman's terms.

"The book talks about a way of life, not just a quick fix. It will shave years off your biological clock."

But, if there is one thing Ariel cannot alter it is time. Or can he?

Gideon Ariel

"Three years ago who had even heard of the women's team? Now, they are the best in the world," said Ariel. Except for China.

The Chinese beat the Americans with what Ariel said is an "average team. Everyone is the same height and proficiency, while our team varies.

"We have 20 rolls of film, each with 400 feet on each athlete in action. We can examine our team's weaknesses and strengths and those of our opponents. We will beat the Chinese when we meet them in 10 months," he predicted.

Cameras play a critical role in Ariel's work. "The human eye cannot judge correctly the speed of the human reaction;" Ariel said. So, he uses highspeed, infra-red film transferred to video tape, inserted into a computer and then digitized so a stick figure portrait of the athlete appears in motion. "Rather than using a human guinea pig, I can simulate every action he may take," he said.

Outlining the video screen with a sonic pen, Ariel spoke of moving the center of gravity, analyzing the inertia on the body and condensing the body