The games robots play are revolutionizing tactics and training

Gideon Ariel is a computer whiz. He's also an athlete and a businessman. At present, he's the nation's foremost proponent of the use of computers in sports

By Unknown in Sports Mirror on Monday, August 1, 1983

The article discusses the use of computers in sports, focusing on the work of Gideon Ariel, a former Olympic discus thrower turned computer scientist. Ariel uses computers to analyze the performance of sports teams and individual athletes, identifying patterns and weaknesses that can be exploited for competitive advantage. His methods have been credited with the rapid rise of the American Women's Volleyball Team. However, some academics criticize Ariel for his commercial approach and for not revealing his methodology. The article also discusses the potential of computerized exercise equipment that can adapt to an athlete's training needs.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

COMPUTERS

The games robots play are revolutionizing tactics and training

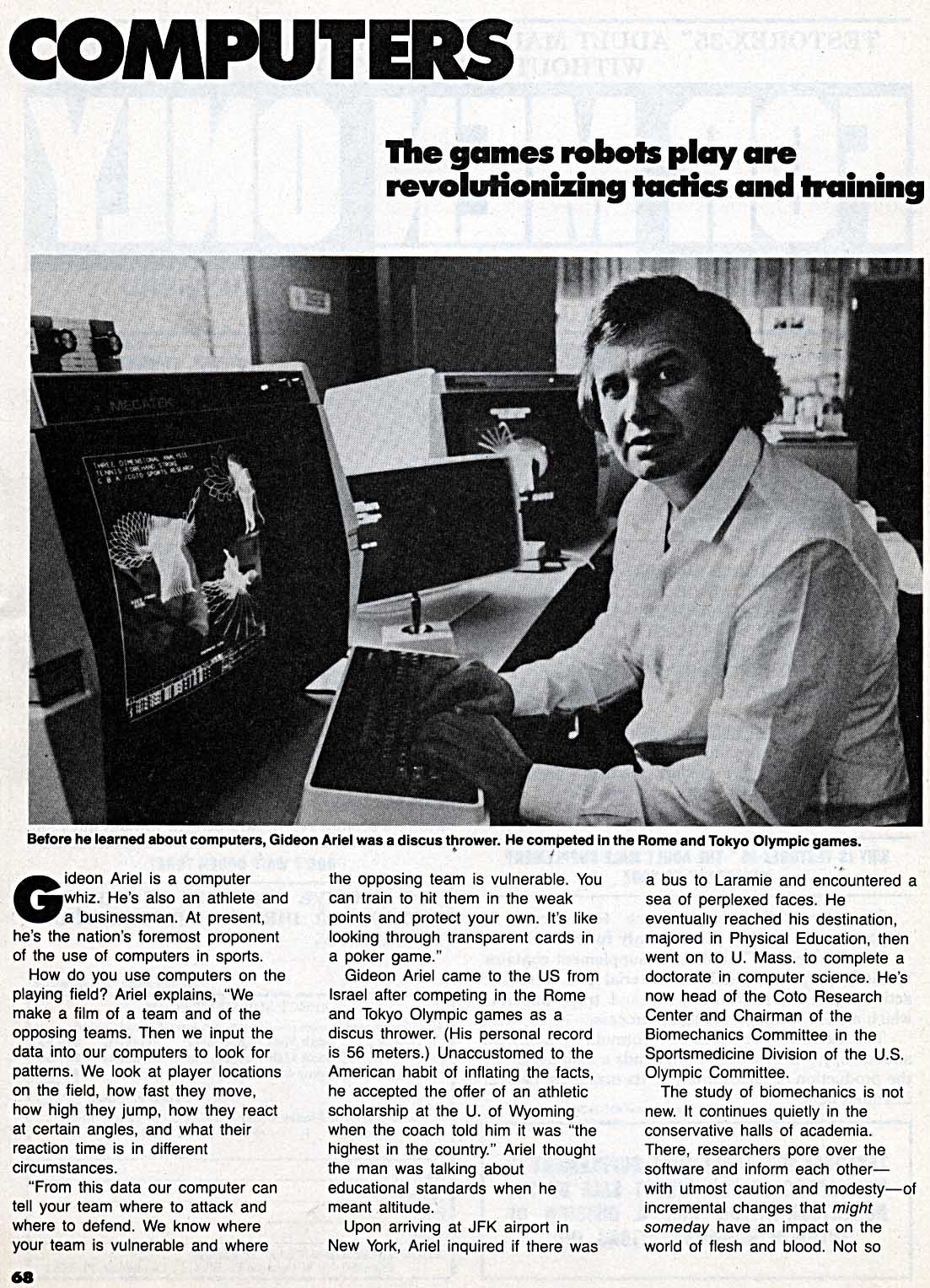

Before he learned about computers, Gideon Ariel was a discus thrower. He competed in the Rome and Tokyo Olympic games.

Gideon Ariel is a computer whiz. He's also an athlete and a businessman. At present, he's the nation's foremost proponent of the use of computers in sports.

How do you use computers on the playing field? Ariel explains, "We make a film of a team and of the opposing teams. Then we input the data into our computers to look for patterns. We look at player locations on the field, how fast they move, how high they jump, how they react at certain angles, and what their reaction time is in different

circumstances.

"From this data our computer can tell your team where to attack and where to defend. We know where your team is vulnerable and where

the opposing team is vulnerable. You can train to hit them in the weak points and protect your own. It's like looking through transparent cards in a poker game."

Gideon Ariel came to the US from Israel after competing in the Rome and Tokyo Olympic games as a discus thrower. (His personal record is 56 meters.) Unaccustomed to the American habit of inflating the facts, he accepted the offer of an athletic scholarship at the U. of Wyoming when the coach told him it was "the highest in the country." Ariel thought the man was talking about educational standards when he meant altitude.

Upon arriving at JFK airport in New York, Ariel inquired if there was

a bus to Laramie and encountered a sea of perplexed faces. He eventually reached his destination, majored in Physical Education, then went on to U. Mass. to complete a doctorate in computer science. He's now head of the Coto Research Center and Chairman of the Biomechanics Committee in the Sportsmedicine Division of the U.S. Olympic Committee.

The study of biomechanics is not new. It continues quietly in the conservative halls of academia. There, researchers pore over the software and inform each otherwith utmost caution and modesty-of incremental changes that might someday have an impact on the world of flesh and blood. Not so

68

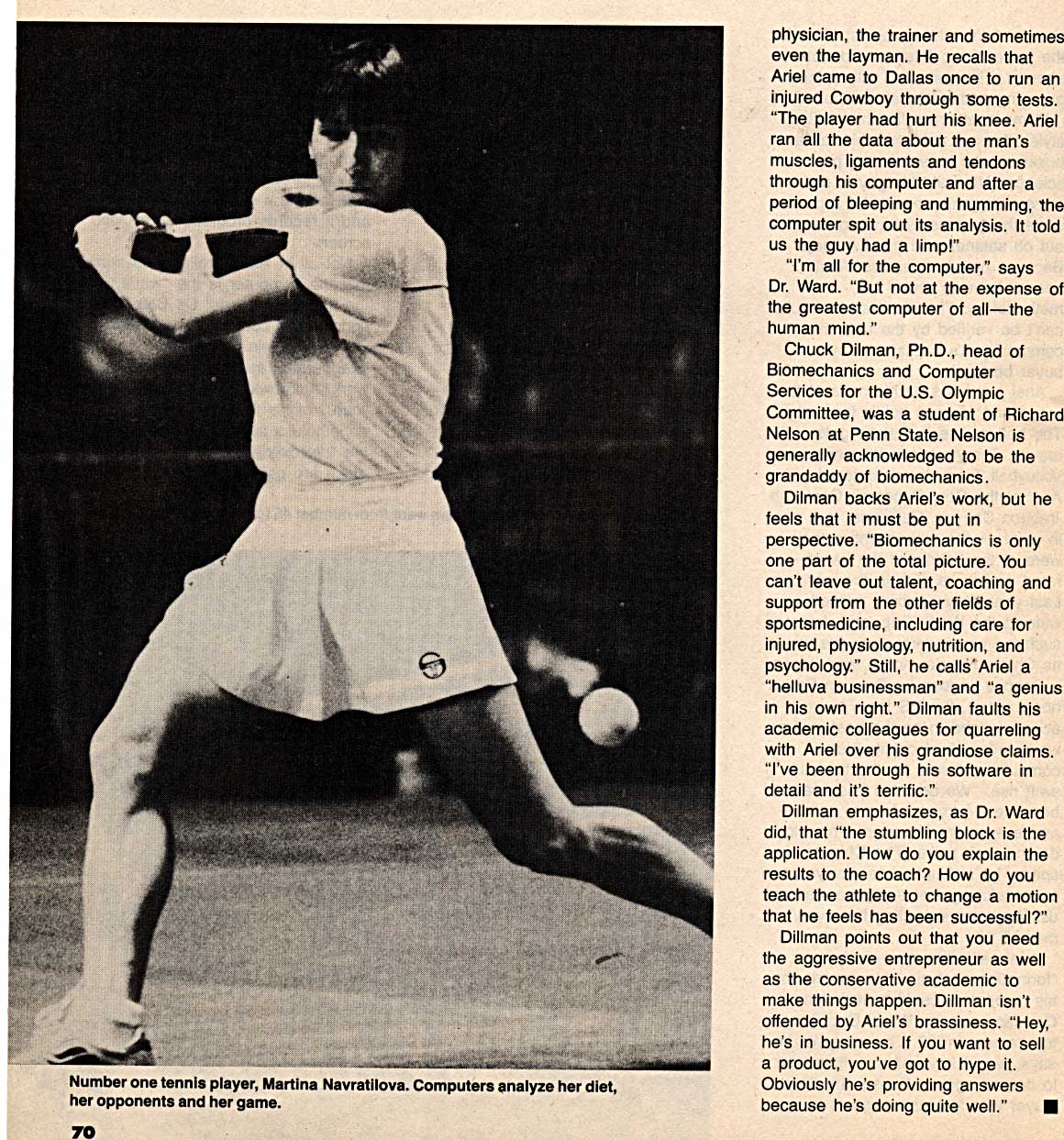

Number one tennis player, Martina Navratilova. Computers analyze her diet, her opponents and her game.

70

physician, the trainer and sometimes even the layman. He recalls that Ariel came to Dallas once to run an injured Cowboy through some tests. "The player had hurt his knee. Ariel ran all the data about the man's muscles, ligaments and tendons through his computer and after a period of bleeping and humming, the computer spit out its analysis. It told us the guy had a limp!"

"I'm all for the computer," says

Dr. Ward. "But not at the expense of the greatest computer of all-the human mind."

Chuck Dilman, Ph.D., head of Biomechanics and Computer Services for the U.S. Olympic Committee, was a student of Richard Nelson at Penn State. Nelson is generally acknowledged to be the grandaddy of biomechanics.

Dilman backs Ariel's work, but he feels that it must be put in perspective. "Biomechanics is only one part of the total picture. You can't leave out talent, coaching and support from the other fields of sportsmedicine, including care for injured, physiology, nutrition, and psychology." Still, he calls'Ariel a "helluva businessman" and "a genius in his own right." Dilman faults his academic colleagues for quarreling with Ariel over his grandiose claims. "I've been through his software in detail and it's terrific."

Dillman emphasizes, as Dr. Ward did, that "the stumbling block is the application. How do you explain the results to the coach? How do you teach the athlete to change a motion that he feels has been successful?"

Dillman points out that you need the aggressive entrepreneur as well as the conservative academic to make things happen. Dillman isn't offended by Ariel's brassiness. "Hey, he's in business. If you want to sell a product, you've got to hype it. Obviously he's providing answers because he's doing quite well."

Gideon Ariel, who trumpets: "This is the wave of the future; no doubt about it. The computer will replace guessing and witchcraft in sports."

Some academics find his bold style offensive and paint him as a huckster who is prostituting pure science: After all, this guy is out there selling his secrets for a profit, while the professors have to sweat it out on salaries and grant money. Because he's in business, Ariel doesn't have to reveal his methodology. That means his results can't be verified by the scientific community. It's capitalism boys: buyer beware!

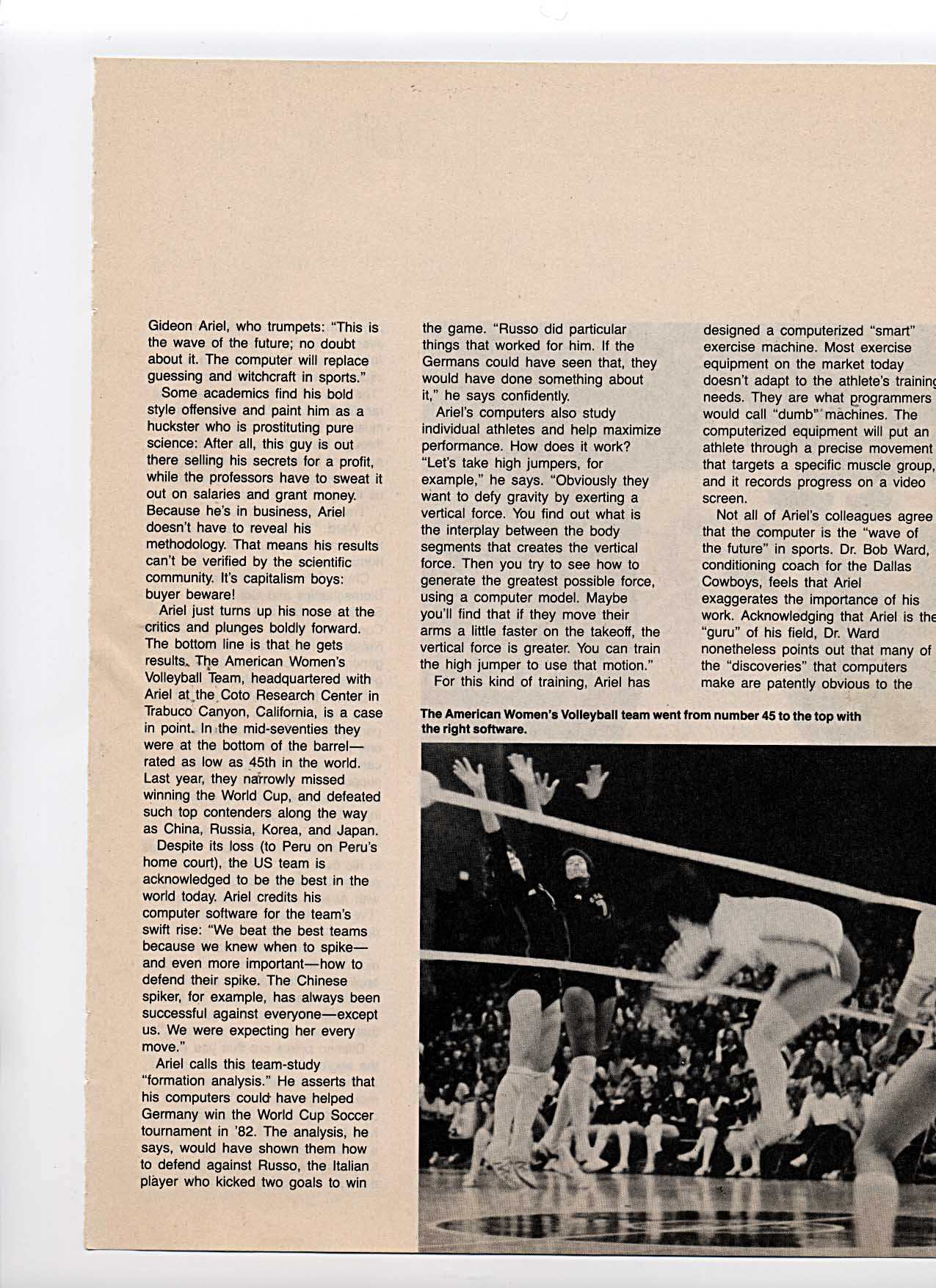

Ariel just turns up his nose at the critics and plunges boldly forward. The bottom line is that he gets results, The American Women's Volleyball Team, headquartered with Adel at the Coto Research Center in Trabuco Canyon, California, is a case in point. In the mid-seventies they were at the bottom of the barrelrated as low as 45th in the world. Last year, they narrowly missed winning the World Cup, and defeated such top contenders along the way as China, Russia, Korea, and Japan.

Despite its loss (to Peru on Peru's home court), the US team is acknowledged to be the best in the world today. Ariel credits his computer software for the team's swift rise: "We beat the best teams because we knew when to spikeand even more important-how to defend their spike. The Chinese spiker, for example, has always been successful against everyone-except us. We were expecting her every move."

Ariel calls this team-study "formation analysis." He asserts that his computers could have helped Germany win the World Cup Soccer tournament in '82. The analysis, he says, would have shown them how to defend against Russo, the Italian player who kicked two goals to win

the game. "Russo did particular things that worked for him. If the Germans could have seen that, they would have done something about it," he says confidently.

Adel's computers also study individual athletes and help maximize performance. How does it work? "Let's take high jumpers, for example," he says. "Obviously they want to defy gravity by exerting a vertical force. You find out what is the interplay between the body segments that creates the vertical force. Then you try to see how to generate the greatest possible force, using a computer model. Maybe you'll find that if they move their arms a little faster on the takeoff, the vertical force is greater. You can train the high jumper to use that motion."

For this kind of training, Ariel has

designed a computerized "smart" exercise machine. Most exercise equipment on the market today doesn't adapt to the athlete's traininc needs. They are what programmers would call "dumb" machines. The computerized equipment will put an athlete through a precise movement that targets a specific muscle group, and it records progress on a video screen.

Not all of Ariel's colleagues agree that the computer is the "wave of the future" in sports. Dr. Bob Ward, conditioning coach for the Dallas Cowboys, feels that Adel exaggerates the importance of his work. Acknowledging that Ariel is the "guru" of his field, Dr. Ward nonetheless points out that many of the "discoveries" that computers make are patently obvious to the

The American Women's Volleyball team went from number 45 to the top with the right software.