Winners

Sports' emerging heroes reach pinnacles of power through science

By Susan Mazur in Omni on Tuesday, July 1, 1980

The article by Susan Mazur discusses the increasing role of science and technology in sports training. It highlights how computer systems are being used to analyze and improve athletes' movements, eliminating flaws that are often overlooked by human coaches. The article also discusses the use of psychology in sports training, with the belief that performance is 20% physical and 80% mental. The use of hypnosis and relaxation techniques to help athletes overcome fears and insecurities is also mentioned. The article further discusses the use of machines like the Cybex and the Nautilus in training, and the resistance of some athletes to these new methods. The article concludes by discussing the future of sports training, including the use of 3D computer simulations and the potential for early athletic conditioning and selection to create a generation of injury-resistant athletes.

Article Synopsis

The article discusses the evolution of athlete selection and training, focusing on the increasing specialization of athletes for specific roles based on criteria such as weight, size, speed, and strength. It highlights how athletes can still overcome body limitations through determination and talent, using the example of world-class bodybuilder Danny Padilla.

The article also explores the role of science in improving athletic equipment, with a particular emphasis on innovations from the space program. It mentions the potential dangers of new equipment, such as foam-lined helmets in football, which have led to more reckless play due to their effectiveness in protecting the wearer.

The article then delves into the controversial topic of enhancing athletic performance through anabolic steroids and the potential for genetic manipulation. It discusses the ethical issues surrounding these practices and the potential health risks associated with steroid use.

The article concludes by looking at the future of sports science, including the possibility of creating genetically perfect athletes and cloning. It emphasizes that while these possibilities may be far in the future, current methods and upcoming innovations will continue to improve athletic performance.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

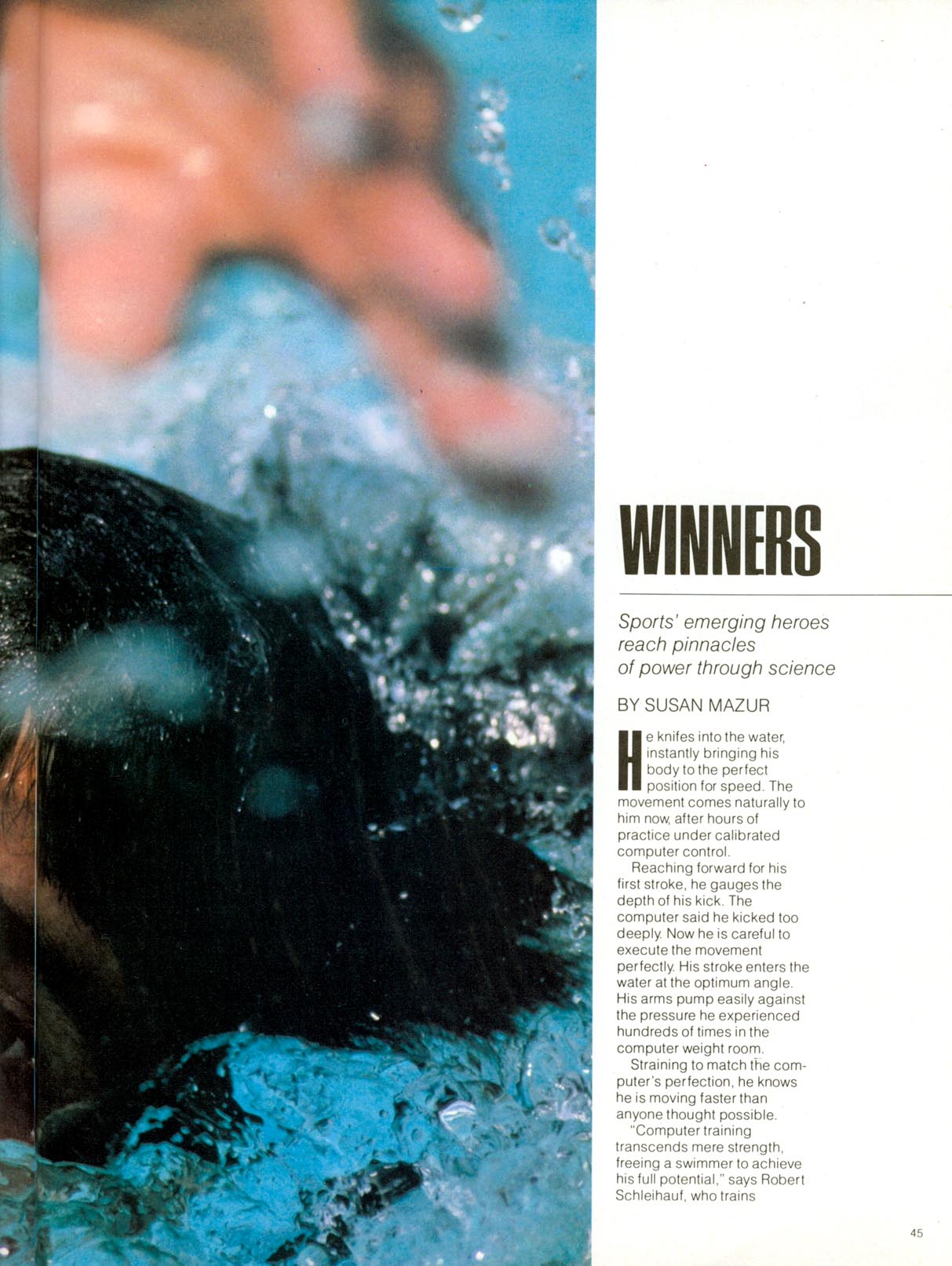

Sports' emerging heroes reach pinnacles of power through science

BY SUSAN MAZUR

e knifes into the water,

intly bringing his Jy to the perfect position for speed. The movement comes naturally to him now, after hours of practice under calibrated computer control.

Reaching forward for his first stroke, he gauges the depth of his kick. The computer said he kicked too deeply Now he is careful to execute the movement perfectly. His stroke enters the water at the optimum angle. His arms pump easily against the pressure he experienced hundreds of times in the computer weight room.

Straining to match the computer's perfection, he knows he is moving faster than anyone thought possible.

"Computer training transcends mere strength, freeing a swimmer to achieve his full potential.' says Robert Schleihauf who trains

GWe can surpass all physicallimits. Computertraining enables us to see movementbeyond human perception.'

swimmers on a computer system at Teachers College, Columbia University. "With the computer we can evaluate each of a swimmer's movements and eliminate all the tiny flaws that the swimmer doesn't notice and the coach can't see. Even Olympic-caliber swimmers can improve their times significantly through our computer training techniques."

Schleihauf uses a computer system devised by Dr. Gideon Ariel, the former Israeli discus hurler, who is now director of computer sciences and mechanics for the U.S. Olympic Committee. "The human eye cannot quantify human movement," he says. "The important

things in performance - the timing, the relative speeds of dozens of limb and body segments, the changes in center of gravity-all must be measured, weighed, and compared scientifically to be of any use."

The future of sport, says Dr. Irv Dardik, of the Council on Sports Medicine, rests in the hands of science. Coaches will become scientists. Computers, behaviorism, biomechanics, and genetics will help create perfectly tuned athletes. New tools will usher in an age in which human perceptions are too limited to train human bodies.

"How can the human eye tell whether an athlete has turned his shoulder a degree too far to the left or stopped a centimeter short when releasing the ball?" Ariel asks. "In fact, it can't. But the computer can evaluate many elements at once."

Ariel's better-than-human eye begins with a camera that shoots an athlete's motion at up to 10,000 frames a second. These high-speed images are projected onto a screen over an array of 20,000 extremely sensitive microphones. A special sonic pen is used to trace the athlete's position in each photo frame. Microphones pick up the signals and relay them to a computer that animates a stick figure on a video screen. The stick figure simulates a full sequence of athletic movements, which can be frozen at any point for observation.

Golf swings and other movements can reach perfection with computer techniques (above), but sweat and desire, as shown by boxer Chuck Wepner (left), are essential for athletic excellence.

Ariel uses this setup to determine an athlete's center of gravity, velocity, acceleration, direction, angle of attack, and force. It gives him a fixed image of the relationship of every part of an athlete's body to every other part at all stages of movement, allowing the tiniest flaws in technique to be studied and corrected without guesswork.

"When a swimmer is working out," he says, "the coach can't tell whether his hand motion produces the most thrust, whether his starting dive is as effective as possible, whether the angle of his arm entry generates the least resistance. We study the athlete in the gym. We test him in flumes with stress pulleys attached so that we can gauge the force generated by many different movements. We create a pattern through the computer of the best possible series of motions. This we compare with the swimmer's performance in the pool. Only then can the coach know exactly where the swimmer is working to best advantage and where he isn't. Before the advent of computers, coaches were merely guessing."

The emerging science of sport will work with athletes' minds as well as with their bodies. It encompasses programs from broad social schemes to minute manipulations of behavior. It is "a holistic approach, utilizing psychology as well as physiology. sociology, and medicine," according to Dr. Marvin Clein, of the Human Performance Laboratory, in Denver.

Already," declares Dr. Jakow Bielski, a psychologist at City University of New York, "it is common today among athletes, regardless of class, to assume that performance is about twenty percent physical and eighty percent mental. This understanding alone typifies a new kind of emerging athlete, one who stands much removed from the inherently physical athlete of time not so far past."

Dr. Bielski points to the mental edge that lifted the American hockey team over the physically superior team sent by the USSR in last winter's Olympic Games as an example of the power of behaviorism in athletics. "However, the real impact of this shift to a more mental, systematic approach to sports," Bielski says, "is yet to be seen. The future athlete will implement behavior-control advancements so that even spontaneity will be controlled."

Right now scientists are looking for ways to assist athletes in eliminating mental blocks and integrating the workings of their minds and muscles. Dr. Richard O'Brien, of Hofstra University, in New York, is using hypnosis and relaxation techniques to help athletes conquer suppressed fears. Dr. O'Brien worked with boxer Duane Bobick, who had the disastrous habit of "freezing up in the first round." O'Brien, employing hypnosis, discovered a seething caldron of fears and insecurities that paralyzed the fighter in the ring. He took Bobick through a treatment of 20-minute tension-relaxation sessions. First, he'd tell the fighter to tense his muscles, then to relax them. Next he'd go on to internalized routines, with Bobick relaxing himself by concentrating on soothing thoughts Finally, Bobick grew so adept at willing himself to relax that he overcame his first-round handicap completely.

Dr. Clein is working on systems to improve athletes' "muscle memory." He believes the athlete rises or falls on a kind of intelligence that Clein calls fluid. O'Brien, a zealous supporter of Clein's ideas, says,

"There are no sports that I know of where you are really cognitively involved. There are no thinking sports. Sports are fluid motion, muscle memory. The proper response has to come from muscle memory because Lord help you if you try to think about anything athletic." Clein probes the body for its information storage-and-retrieval potential much as a neurologist probes the nerves. Clein links athletes to a host of measuring systems with electrodes, noting the range of muscle-nerve responses as the athletes make athletic choices.

Bielski takes a slightly different position. "The ability to switch from the fluid state to the cognitive and vice versa is where the real power lies." he says. "This is what separates the supple. successful Roger Staubach-type athlete from the stiff Duane Bobick-type. The power of switching marks the great performer. The ability to alter the game plan by quick-thinking strategy, as well as by recalling a learned repertoire of techniques. To follow rushes of confidence with the knowledge of when to stop and ask. 'What am I doing? What is my opponent doing? What is going on in this situation?' All without ever losing sight of the point. successful performance."

Even the physical side of sports science will have a positive mental impact on athletes. New training systems that achieve better conditioning for athletes also generate enormous confidence because of their scientific precision and efficiency. The athletes are not simply in better shape, they know they're in better shape. and so they perform without worry.

Ariel's Wilson-Ariel 4000, which the Dallas Cowboys will use this season, actually puts the computer in charge of the player's training. Ariel's unit monitors hydraulic lifts that function like barbells, except that their pressure can be fine-tuned to maximize a player's workout. A physical profile cassette is made for each athlete, relating his strengths, weaknesses, body peculiarities. and fitness goals. The computer uses this profile to adjust the pressure, speed, and duration of the 4000's drills. It can. for instance, help an athlete build up a postsurgical knee by presenting it with the most appropriate amount of pressure each day. while keeping the other leg from going soft by challenging it with the full training weight. This individual programming. Ariel asserts. cuts down on training time, gives the athlete confidence in his training regimen. and allows coaches to train each part of an athlete's body to absolute specifications for his particular task.

"The 4000 gives you a lot more information." Ariel says. "and it tells you how you're progressing. It will let you know if you're lazy or if you should try harder. It'll even remind you if you haven't paid your gym dues for the month."

The Hilton hotel chain. Ariel claims. is thinking about putting 4000's in all its health clubs so that travelers can get perfect workouts through their computer cassettes. no matter where they may be.

48 OMNI

The next frontier, envisioned by Ariel, will be three-dimensional computer simulations of athletic motion. Not exactly holograms, these images will be 3-D views projected on a two-dimensional screen. Like computer-generated engineering perspectives, they will give the illusion of three-dimensionality.

"By using a hologram, you'd really see the figure in 3-D. utilizing optical prisms and things like that," Ariel says. "And we will see that in the near future, no question about it. You'll be able to step right into a hologram to simulate the movements of an Olympic champion. We are working on that now"

Ariel's work may represent sports' next destination, but quite a few trainers and athletes haven't gotten there yet. They prefer training techniques that, while new, aren't as far out as prancing stick figures. The most popular among these is the Cybex machine, a spin-off from Skylab that has found wide acceptance with professional basketball and football teams.

The willingness to use new technologies and ideas represents the coming wave in coaching that many believe will soon bridge the gap between scientific needs and athletic habits'

The Cybex uses a technique called isokinetics. which means that the harder you push. the more resistance you meet. like running your hand through water. The Skylab astronauts used the device to keep limber in their confined space. Now earthbound athletes have found it an adaptable and effective conditioning tool.

Bob Reese. trainer of the New York Jets. uses the Cybex as part of his predraft physical to determine an athlete's range of joint motion and muscle strength. By pinpointing gaps in muscle strength -such as more than a 10 percent strength difference between legs-the Cybex can weed out injury-prone players and train their weak muscles into playable form.

Mike Saunders. trainer and physical therapist for the New York Knicks. lauds the Cybex's flexibility and precision. -We can set it for revolutions per minute or degrees per second. and an athlete can work out at all various speeds. We can calculate how many foot-pounds of torque are produ^ed by a muscle group Mid! s important is to get a base line that serves as the comparison level of an athlete's basic health or injury. If he is injured. we can work him out on the Cybex, comparing body strength from session to session until he's matched his base line. Then we know he's fit. Then he can play."

According to Saunders. Cybex is doubly beneficial. It offers physical advantages of swift, controlled training and the confidence of mind that one's training is doing what it's supposed to do.

-In the case of Hollis Copeland [of the Knicks I." Saunders says, "we used the Cybex to increase the strength of certain muscles while we rehabilitated his slightly injured ligaments. We used knee flexions and extensions at slow speed both to build up the old injury and to make a new injury less likely. Later we compared his left leg to his right leg in terms of strength and then looked at the original base line. Hollis saw his chart and was satisfied that he was okay to play The fact that an athlete can see his own readout from the Cybex is another important feature of the machine and of the athlete's healing process."

Some sports diehards still stick with the most modest advance in training gear. the Nautilus, a contraption that links the common types of weightlifting movements into a single unit. The athlete can perform all his exercises in one place without fear of dropping weights and without the need for spotters to lift and lower barbells.

"I don't believe in anything but the Nautilus." says boxing manager Dave Wolf. "I am aware of other sorts of machines. but the Nautilus is the only one I'll use."

One reason why some athletes lag behind in using new training methods. Saunders thinks. is that they feel like human guinea pigs. under the thumb of jargonbabbling scientists who don't really care about their problems. If information from scientific testing could be made more intelligible to athletes. Saunders believes. more would use it. "It is. after all. not the computer that does the work." he notes, "but the people who interpret the information. And that information could really help athletes, or it could just help some doctor publish articles in journals that few people would understand."

Some athletes' skepticism about new methods has hardened into downright disbelief. "I just don't believe Ariel's system is possible." states Mike O'Shea. owner of the New York Sports Training Institute. Kayaker Steve Kelly one of O'Shea's athletes, adds. "I think it's hogwash. Most of the findings in my event could have been deduced by simply watching movement with the naked eye." Ariel counters that Kelly and other kayakers didn't work with the computer long enough to obtain significant results.

Others point out that. no matter how effective new training machines may be, they still can't overcome the enormous influence of mental states on sports figures. In some cases, in fact. the machines can be mentally devastating for an athlete.

Consider bike racer Paul Deem. who won a Pan-American Games gold medal while still a teen-ager. then captured an

CONTINUED ON PAGE 91

WINNERS

CQNTINUF P FROM PAGE 48

unprecedented three U.S. national championships. Before the 1978 Nationals. Deem and other participants went through a sophisticated battery of evaluations and tests. The testers told Deem that his oxygen-intake levels, a vital measurement for a biker, simply didn't measure up to world class standards. Although his body hadn't changed a whit, Deem never won a major competition after that scientific pronouncement. The precise technological evaluation made it psychically impossible for him to compete at the top of his sport.

Still, those in the profession believe. the benefits of the new ideas and technologies far outweigh their drawbacks. As coaches become more familiar with biomechanical evaluation, the gap between scientific needs and athletic habits will narrow. Roger Counsil. coach of Olympic gymnast Kurt Thomas, notes. "Coaches have grown in their ability to analyze the mechanics of sport. This allows us to teach greater difficulty with greater safety. We have coaches more competent today than there have ever been. The training methods for coaches have changed; now they emphasize biomechanics and computer analysis. As coaches become more familiar with sports science. they'll be better able to get athletes to understand and use it "

O'Shea. however, feels scientistcoaches can have only limited influence on sports unless there's a societywide system that encourages athletic development. "I think the Olympic Committee needs to get down to earth. profiling youngsters at an early age, as the East Germans do, instead of working with computers and athletes after the athletes have already achieved a successful style of performance. I'd like to see Bruce Jenner cartoons for kids

In San Francisco psychologist Joan Barnes is taking a first small step in this direction. Her Kindergym is loosely modeled on the East German system of scientifically stimulating athletic achievement from earliest childhood on. A "noncompetitive. free-form play environment," Kindergym takes children from three months to four years. accompanied by a parent. and "guides them through development of body and spatial awareness, eye-hand coordination, locomotor skills. and gross and fine muscle development." Children run, jump, climb, and crawl around at their own pace to lively musk. They work out with brightly colored, toddler-size equipment made of aluminum, molded plastic. and wood. They can choose from various gym gear, such as tunnels. tumbling mats. stacks of inner tubes. walk-up slides. trampolines, ramps, balance beams. bars, bells. scooters. and silk parachutes.

The problem with this kind of early development system is that the young athletes must retire their numbers so soon. There aren't adequate follow-up programs After graduating at age four, youngsters often do not confront scientific training and coaching again until high school.

Earlier athletic conditioning and selection would create a generation of injuryresistant athletes, a greater contribution to sports than anything else science has provided so far. Dr. John Marshall, who was the chief sports doctor for New York City's schools and numerous professional teams until he died in a plane crash this spring, said. "Despite all the advances, we sports physicians and surgeons lust haven't created anything new in terms of concepts. What we do are merely things that have been done for at least a couple hundred years. We refine them. We polish them. We improve the technical aspect. But the same injuries occurred twenty-five years ago that we see today. Not all physicians appreciate that. We can't really say we've made progress until we weed out these recurring injuries. We need to prepare the young for injury-free performance."

Already the concept of careful cultivation and selection of athletes has made serious strides in professional ranks. Today's pro is a far different creature from his predecessors because he has been crafted differently by his environment.

"He's taller, quicker, stronger," says John Mazur. defensive coordinator for the New York Jets. "He's had better programs when young, better foods, more opportunities for weightlifting. Even a few years ago weights were taboo - Nautilus. the whole bit."

Bill Hampton. the Jets' equipment manager. says. "Fifteen years ago a twentyeight-inch waist was unheard of. They were all thirty-four to forty-two inches. Today kids are perfect specimens-six feet three, two hundred forty-five pounds, thirty-four-inch waist. I don't know whether it's nature or just that the new generation wants to be able to fit into their Jordache jeans or what."

This change in athletes isn't so much the result of improvement in the human species as it is in techniques of selection and preparation "Evolution will change things, but that takes hundreds of thousands of years to occur," Dr. Marshall said. "For one tiny change in a bone or for one little ligament to migrate from one place to another -. these go way beyond practical planning strategies. So the changes we see now aren't genetic."

Marshall cited football as an example. A few decades ago teams had 32 players. who played on both offense and defense. Today each position is highly specialized. and each athlete is tailor-made for his task. Marshall explained how improved methods of selection helped to bring these changes about.

"Now you have a one-hundred-seventyfive-pound defensive back who has great hands and plays a lot of sports very well. Then you have a two-hundred-seventyfive-pound offensive lineman who doesn't have the quickness, but he has bulk and a lot of momentum. You have widely divergent athletes on the same team. We select

players now for specific criteria. We look for weight, size, forty-yard speed, vertical jump, muscle-fiber type, upper-body strength, lower-body strength, and more. If a player has just a few things to do exceptionally well, his performance ought to be better."

Despite this specialization, an athlete still can overcome body limitations and succeed in a sport through sheer determination and talent. Danny Padilla, for example, is a world class body builder at the improbable dimensions of five feet two and weighing 180 pounds. In New York last year Padilla used style and what he calls "the most symmetrical body in the world" to beat out the brawny behemoths.

The point is that optimum curves of performance and body type are based on specific ideas about what and how an athlete should perform. A new idea relating to performance can create a wholly different concept of the -perfect athlete" for a particular event. A good example is the invention of the Fosbury Flop for high jumpers, which shifted the emphasis from tight, muscular leapers to loose, angular types with lean, aerodynamic lines. Even with all the advantages of computer selection, athletics remains a subjective, dynamic science.

Apart from training and selection. science has helped athletes by improving their playing equipment. The space program. which has been a sports innovator ever since the development of the hang glider in the 1950s, has played a significant role in improving athletic equipment.

A report by astronaut James A. Lovell, Jr.. in Aviation, Space and Environmental Medicine magazine, for example, lists lightweight sportsman's blankets and jackets, sleeping bags, and ski parkas made from "the aluminized plastic originally devised to keep cryogenic fluids cold in space" as among the benefits accruing to sports from space exploration. The report also mentions rechargeable heated gloves and ski boots, light composite materials for golf clubs and fishing rods, and antifog compounds that keep diving masks as clear as they once kept spacecraft windshields.

A new silicon plastic foam from NASA that takes the shape of impressed objects but returns to its original contour after even 90 percent compression is being used for football headgear Looking forward, enormous possibilities loom for NASA's recently patented portable breathing system. Designed for zero-g use. it reconditions air using lithium oxide in a sealed system.

The success of these NASA developments has caused some never-beforedreamed-of problems. In football, for example, the foam-lined helmets have proved so effective at protecting the wearer that players have begun using their heads as battering rams against opponents. With older helmets. the impact of a head-on crash would bother both players involved, but the new helmets allow huge linemen to slam their heads recklessly into the ribs and spines of halfbacks and wide receivers. Hampton likens the situation to a Volkswagen getting juiced by a Cadillac.

Fortunately, no such problems have arisen with NASA foam-lined shoes. Tennis star Jimmy Connors and the New York Knicks have found that the plastic, which molds to the exact shape of the wearer's foot and which doesn't slide against the skin, has reduced footaches and injuries and has made them better performers.

Beyond all the prosaic advances in training, attitude. selection, and equipment lies a realm of possibilities about the zenith of sports science. creation of a perfect athlete through genetic manipulation and drugs. The current controversy over improving athletic performance through anabolic steroids is only a small-time indication of the kinds of manipulations that may lie ahead.

Steroids are hormonal compounds believed to increase training's effects and an athlete's aggression if taken in huge. sustained doses. After the East German female athletes trounced all comers in the 1968 Olympics. amid rampant rumors that they had stuffed themselves with steroids, the practice caught on with athletes everywhere. The reason is fundamental: The athletes believe the compounds will better their performances.

"By taking anabolic steroids," writes Dr H. Howald, "one hopes for improved protein synthesis in the body and consequently muscle growth, such as would not be possible through physical training alone, no matter how intense.'

The expanding popularity of steroids raises some concern that the Summer Olympics in Moscow with or without the Americans, may prove to be a competition among drug companies. The glamour attached to winning and the lure of big money from commercial endorsements are attracting athletes even down to the high-school level toward steroids.

Dr. Gabe Mirkin. in his Sportsmedicine Book, admits. "So pervasive has the practice become that professional. college. and even high-school football coaches routinely dispense steroids."

Jan Sieffer, who trains Olympics-bound gymnasts, claims that some members of the wrestling and swimming teams at Rutgers University. in New Jersey. used steroids a few years ago when he was there. Ariel, who was at the 1976 Summer Olympics in Montreal. says. "If you were in the weight events you wouldn't even make the trials if you weren't taking steroids. In the shot put the difference between those on steroids and those not was as if one group was putting sixteen-pound shots and the other was putting forty-pound shots."

Both Ariel and Dardik are convinced the use of steroids is widespread in the United States Then. it may be asked, why hasn't the phenomenon been investigated by

92

OMNI

medical authorities? Why aren't there studies about the best uses of this potentially dangerous drug?

"There are a couple of reasons why" Dardik says. "The main one is an international law about experimenting with humans. It is necessary for someone to give consent now. but the critical point is that even with consent, the work must be justified. Can it be justified to see whether you can improve an athlete's performance by using drugs? The only real justification for using drugs is for medical purposes, and here you're giving an athlete anabolic steroids, potentially harming him, just so he can win medals or break records. How can you justify that? There were studies in the past, but they've stopped."

The outcry against the drugs-which carry the potential for later heart and liver ailments, among a host of other ills-has led some to consider the possibility of obtaining similar results through genetics Drugs. after all, are merely an artificial means to shift hormone levels set by the genes in the first place. It you could manipulate the genes. you could create a pumped-up athlete without the bad side effects of drug use, and without raising ethical questions.

This has deepened into a question of when science will be able to produce enough genetic control to engineer the genetically perfect athlete each trait selected to provide ultimate performance

Such possibilities lie far in the future, according to Dr. Norton Zinder. a geneticist at Rockefeller University, in New York City. Dr. Zinder notes, though, that "while these things are impossible to do physically today, they can be thought about. This is actually what frightens those people who like to get frightened, that we can even think about such things. You can't say we won't be able to do it someday. In fact, most people say sooner or later we will. But you can't put a time on it."

Now geneticists can identify a few specific genes and have the basic technology for transferring a specific gene from one cell to another. But that doesn't help much with sports. Zinder explains. "You don't expect there's a single gene that says make me an eye or make me a knee. And even if there were. within our genetic material there are millions of genes. How in blazes do we find out which one in that million is the one for the eye?"

Half-seriously Zinder advocates an approach to genetic athletic creation that will bring results far sooner "Selective breeding. If it works for sheep. goats, and cows, it'll work for humans. and in a few generations we'll have a lot more athletes. Unfortunately, this requires a tyrant if it is to succeed. The farmer is tyrant to his bulls and cows. Freedom versus efficiency It may be paradoxical, but it's the choice we have."

A new choice for maintaining high athletic levels may be cloning Even football players. such as guard Doug Van Horn of the New York Giants. look forward. to the day "when I can send my clone in to o it for me."

"That. of course. is science fiction." says Dr. John Rainer, chief of psychiatric research. medical genetics. at New York State Psychiatric Institute. in New York City. "But will it ever be possible to actually take an athlete. take his cell, take a fertilized ovum, take out the nucleus. and replace it with the nucleus from the athlete's cell to grow into an exact duplicate of the athlete? It's not around the corner, not twenty-five or fifty years. but maybe in a hundred years. After all, it you can send a man to the moon, I suppose you can clone a human bung."

While we wait for cloned and genespliced champions to appear, we can warm ourselves with the knowledge that present methods, and those just ahead, will continue to produce ever-improving levels of athletic achievement. For the moment our athletes' genes will remain unchanged, but science's impact on all aspects of sports will bring their performances ever closer to the ultimate those genes allow their bodies to attain

"I've learned there is no such thing any longer as a physical limit." Counsil says. "It's the nature of the human animal to improve constantly What I thought were limits have now been passed. If there is an end to what we can do, it's not within my comprehension' 00

94 OMNI