MD aims to improve nation's health using Olympic athletes as 'walking fitness labs'

Vascular surgeon Dardik and computer scientist Ariel are collaborating at the Squaw Valley Sports Medicine Center

By Roy Petty in American Medical News on Monday, August 1, 1977

MD Aims to Improve Nation's Health Using Olympic Athletes as `Walking Fitness Labs'

In 1977, vascular surgeon Irving Dardik and computer scientist Gideon Ariel collaborated at the Squaw Valley Sports Medicine Center to study physical fitness using Olympic athletes. Dardik, a former top-notch sprinter, developed a coronary bypass graft technique using human umbilical cords. However, he was more interested in preventing heart disease than treating it.

The U.S. Olympic Committee appointed Dardik to set up the first of several Olympic Sports Medicine Institutes. The goal was to help Olympic-caliber athletes learn more about their bodies and improve the nation's physical fitness.

Ariel, a former Olympian, used computer technology to analyze athletes' movements and improve their techniques. His work helped discus thrower Mac Wilkins break the world's discus record. Ariel's computer analysis also had applications outside of sports, such as helping people with leg prostheses walk normally.

Dardik and Ariel also addressed the widespread use of anabolic steroids among athletes, calling for more research into their long-term effects. They criticized the lack of interest in sports medicine in the U.S. and called for more corporate support.

Dardik also set up a foundation in Englewood, N.J., using Olympic athletes to train juvenile diabetics. The program improved the kids' cardiovascular condition and reduced their insulin needs. Dardik planned to expand the program and set up more sports medicine institutes around the country.

Tip: use the left and right arrow keys

American Medical

AUGUST 1, 1977

MD aims to improve nation's health using Olympic athletes as `walking fitness labs'

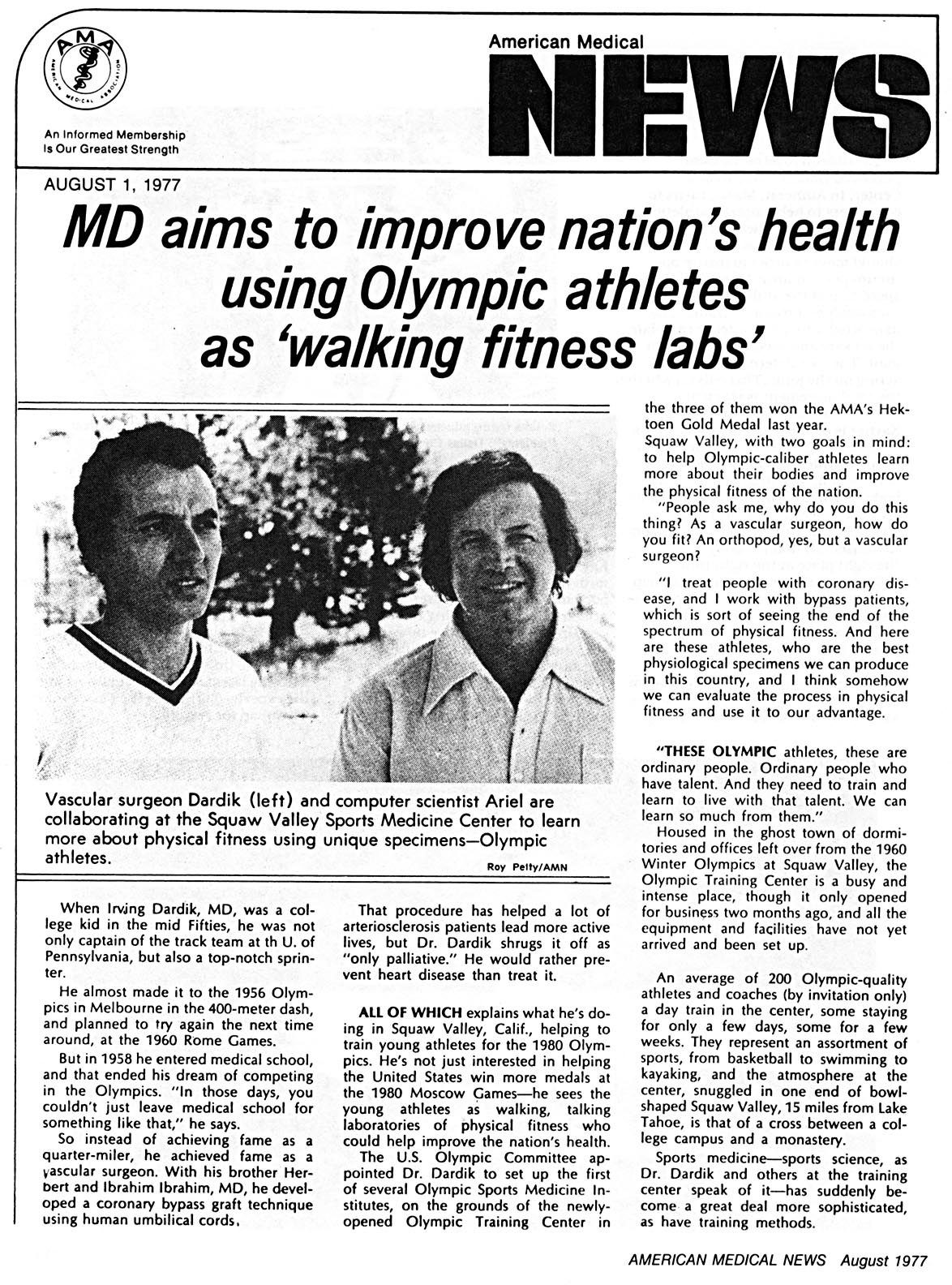

Vascular surgeon Dardik (left) and computer scientist Ariel are collaborating at the Squaw Valley Sports Medicine Center to learn more about physical fitness using unique specimens-Olympic athletes.

When Irving Dardik, MD, was a college kid in the mid Fifties, he was not only captain of the track team at th U. of Pennsylvania, but also a top-notch sprinter.

He almost made it to the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne in the 400-meter dash, and planned to try again the next time around, at the 1960 Rome Games.

But in 1958 he entered medical school, and that ended his dream of competing in the Olympics. "In those days, you couldn't just leave medical school for something like that," he says.

So instead of achieving fame as a quarter-miler, he achieved fame as a vascular surgeon. With his brother Herbert and Ibrahim Ibrahim, MD, he developed a coronary bypass graft technique using human umbilical cords,

That procedure has helped a lot of arteriosclerosis patients lead more active lives, but Dr. Dardik shrugs it off as "only palliative." He would rather prevent heart disease than treat it.

ALL OF WHICH explains what he's doing in Squaw Valley, Calif., helping to train young athletes for the 1980 Olympics. He's not just interested in helping the United States win more medals at the 1980 Moscow Games-he sees the young athletes as walking, talking laboratories of physical fitness who could help improve the nation's health.

The U.S. Olympic Committee appointed Dr. Dardik to set up the first of several Olympic Sports Medicine Institutes, on the grounds of the newlyopened Olympic Training Center in the three of them won the AMA's Hektoen Gold Medal last year.

Squaw Valley, with two goals in mind: to help Olympic-caliber athletes learn more about their bodies and improve the physical fitness of the nation.

"People ask me, why do you do this thing? As a vascular surgeon, how do you fit? An orthopod, yes, but a vascular surgeon?

"I treat people with coronary disease, and I work with bypass patients, which is sort of seeing the end of the spectrum of physical fitness. And here are these athletes, who are the best physiological specimens we can produce in this country, and I think somehow we can evaluate the process in physical fitness and use it to our advantage.

"THESE OLYMPIC athletes, these are ordinary people. Ordinary people who have talent. And they need to train and learn to live with that talent. We can learn so much from them."

Housed in the ghost town of dormitories and offices left over from the 1960 Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley, the Olympic Training Center is a busy and intense place, though it only opened for business two months ago, and all the equipment and facilities have not yet arrived and been set up.

An average of 200 Olympic-quality athletes and coaches (by invitation only) a day train in the center, some staying for only a few days, some for a few weeks. They represent an assortment of sports, from basketball to swimming to kayaking, and the atmosphere at the center, snuggled in one end of bowlshaped Squaw Valley, 15 miles from Lake Tahoe, is that of a cross between a college campus and a monastery.

Sports medicine-sports science, as Dr. Dardik and others at the training center speak of it-has suddenly become a great deal more sophisticated, as have training methods.

Roy Pelty/AMN

Athletics as science

U.S. sports medicine neglected, MD says

INSTEAD OF pot-bellied men in sweatshirts and whistles telling everybody to run laps, there are people like Gideon Ariel, PhD, a computer scientist from Amherst, Mass., who competed in two Olympiads (1960 and 1964, as a discus thrower for Israel), and who now does amazing things in the field of biomechanics.

Dr. Ariel figured out a way of taking motion pictures of athletes performing typical sports maneuvers (a basketball player making a jump shot, for exam, ple), and translating the crit'cal body motions onto a computer grit.

The computer analyzes the athlete's movements, step by step, and produces a thick printout that in essence compares how the athlete perfcrmed the maneuver with the theoretically "perfect" way to perform the maneuverdemonstrating exactly how, and where, the athlete should modify and improve his technique.

It works. Earlier this year, discus thrower Mac Wilkins came to Dr. Ariel's Amherst lab and went through the whirling, ballet-like motions of the discus throw for the benefit of Dr. Ariel's high-speed camera.

WILKINS HAD been throwing the 16-pound di-c about 216 feet lately, but the computer said he should be throwing it 250 feet, and spotted a point where his left leg was working the wrong way, against the throwing motion instead of with it.

Wilkins corrected the error and, two days later, broke the world's discus record with a 232-foot throw.

Dr. Ariel's computer can be used for much more. He displayed an inch-thick printout analyzing the standard shooting and passing motions of four women basketball players bound for the Olympics.

He has a 10,000 frames-per-second camera that can analyze the way a tennic ball strikes the racket. Ir case you're interested, a tennis ball touches the strings of a racket for only .004 seconds, so that the "thump" you feel in the racket is not the ball-it's the reaction of the strings themselves, which is much longer lasting.

Biomechanics, like other phases of sports science, has applications outside athletes, too. Dr. Ariel used the same camera-computer technique to figure out how people with leg protheses can be made to walk without the limping, body-twisting motion common among those with artificial legs.

THE COMPUTER churned out a quick answer: for a person with an artificial left leg, put an eight-pound weight on the right arm. Then he'll walk easily and normally.

"There's so much we can learn from these kinds of applications. Things like that, about biomechanics, that coaches and athletes just aren't aware of. The use of the arms, for example.

"You can use your arms to lift your body off the floor. I weigh 220 pounds and, see, I can lift my feet off the floor, just by using my arms." He demonstrated, swinging his arms up sharply, lifting his muscular, fullback-sized body an inch or two off the ground.

Computer man Dr. Ariel and surgeon Dr. Dardik get along famously, each calling the other "a genius," falling into animated conversations about groundbreaking new research while watching films of sticklike figures on a computer grid, uncoiling in slow-motion jump shots.

"WHEN I WAS A physician at the last Olympic games, athletes would come up to me with questions about training, about nutrition, about drugs. That's what gave me the idea to talk to the U.S.

Olympic Committee about setting up the institutes. There are so many things we don't know about."

Anabolic steroids, for example-the hottest question in O1,, mpic sports right now. Both Dr. Dardrn and Dr. Ariel testify that use of the strength-increasing hormones is widespread in this country, and universal in some other countries, though neither physicians nor athletes know how dangerous they might be.

"In the last Olympic trials," Dr. Ariel said, "if you were in. the weight events (shot put, discus throw, and hammer throw), you wouldn't even make the trials if you weren't taking steroids. In the shot put, the difference between those on steroids and those not was as if one group was putting 16-pound shots, and the other was putting 40pound shots."

Dr. DARDIK isn't sure steroid use is that widespread, but it is certainly a problem. "If an athlete asks me, should I take steroids, I would say no. But we don't really have enough information on it one way or the other. People are manipulating their bodies, and we don't know what the long-term effects are."

That's a result of the apparent lack of interest in sports medicine in the United States, he and Dr. Ariel believe.

"The technology is there," Dr. Ariel remarked. "This country has the talent, big corporations could provide all the equipment and funds we need, just as a donation."

He pointed out that there were plenty of companies in the United States who make pulmonary function equipment like the one recently donated to the training center-but the one donated came from a West German firm, given to the U.S. Olympic Committee.

"People think athletics is an art. But it's really a science," Dr. Ariel said. "If nobody cared whether you won a gold medal or not, if you weren't competing against others, then maybe you could call it art.

"BUT THE MOMENT you put a stopwatch or a measuring tape to something, it becomes a science."

Dr. Dardik adds that the goal of the institute is a lot broader, and a lot more distant than merely the 1968 Moscow games.

"We're not just a bunch of jocks up here, training for the next Olympics," he declared, pointing out there had already been a spinoff from the program in his own backyard.

Dr. Dardik has set up a foundation in Englewood, N.J., using Olympic athletes to work "one on one" with juvenile diabetics. With the help of the American Diabetes Assn. and the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, diabetic kids (along with children with other illnesses, including psychiatrically disturbed kids) were being taken through fitness training programs conducted by the Olympic athletes.

The point was to develop in the kids better cardiovascular condition, to reduce their otherwise elevated chances for arteriosclerosis later in life, he said.

BUT THE SID[ effects had been equally worthwhile: the youngsters' insulin needs were lowered sharply, for example, and all of them felt better, looked better, and displayed much greater selfconfidence as a result of the Olympic fitness program.

Now he has bigger plans. He wants to expand the diabetic fitness program, and he's planning (with the assistance of the U.S. Olympic Committee) to set up as many as six sports medicine institutes around the country. One is now being developed in Colorado Springs, Colo., with the cooperation of the Air Force Academy, and another will be set up in the East next year. -Roy Petty'

AMERICAN MEDICAL NEWS August 1977